Zoom for Mac makes it too easy for hackers to access webcams. Here’s what to do

One of the easiest ways to tell if someone is a practitioner of computer security is to look at their laptop. If the webcam is covered by tape or a sticker, they likely are. A recently published report on the Zoom conferencing application for Macs underscores why this practice makes sense.

Researcher Jonathan Leitschuh reported on Monday that, in certain cases, websites can automatically cause visitors to join calls with their cameras turned on. It’s not hard to imagine this being a problem for people in their bathrobes or in the middle of a sensitive business conference since a malicious link would give no warning in advance it will open Zoom and broadcast whatever is in view of the camera.

Zoom developers almost certainly intended the behavior to make it easier to use the Web conferencing app. But unless users have properly tweaked their settings in advance, Lietschuh’s findings show how miscreants can turn this ease-of-use against unwitting users. A proof-of-concept exploit is available here, but reader be warned: depending on your Zoom settings, your webcam may soon be transmitting whatever it sees to perfect strangers.

“This vulnerability allows any website to forcibly join a user to a Zoom call, with their video camera activated, without the user’s permission,” Leitschuh wrote.

Leitschuh is mostly correct there. Clicking the link will automatically open Zoom and join a call. But as mentioned earlier, video is collected only when Zoom is configured to begin conferences with a camera turned on. Some media reports and social media commentators have said this behavior allows websites to “hijack” a Mac webcam. I’d argue that’s a stretch since (1) it’s fairly obvious that Zoom is opening and broadcasting whatever the camera sees and (2) it’s easy to immediately leave the conference or simply turn off the camera.

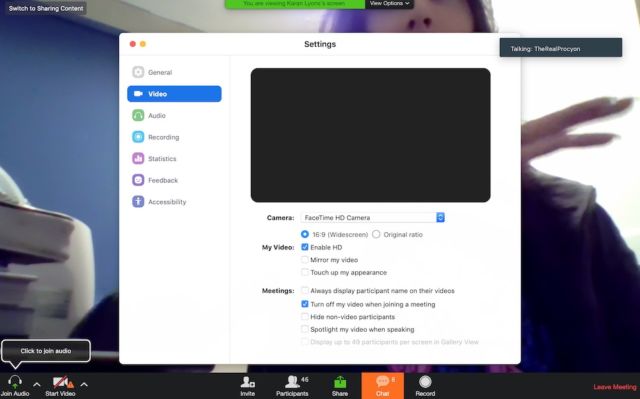

What’s more, preventing the video grab involves a one-time click to a box in the Zoom preferences that keeps video turned off when joining a video. But user beware: even when this setting is on, sites still can force Macs to open Zoom and join a conference.

That’s not to say the threat Leitschuh disclosed is mere handwaving. It’s not. But it underscores the near-impossible balancing act developers must strike. Make a feature too hard to use and people will move to a competing product. Make it too easy and attackers may abuse it to do bad things the developer never imagined.

In this case, Zoom developers should have warned that the ability to automatically join a conference with video turned on was a powerful feature that could be used to compromise users’ privacy. Instead, the developers left it up to users to decide with no up-front guidance. (By contrast, audio is automatically turned off when joining a Zoom conference.) In other words, Zoom developers made this automatic webcam joining way too easy. In retrospect, thanks to Leitschuh’s post, that’s easy to see.

In a response to Leitschuh’s disclosure Zoom’s Richard Farley said the company will roll out an update this month that will “apply and save the user’s video preference from their first Zoom meeting to all future Zoom meetings.” Farley didn’t say if Zoom will provide the guidance many users will need to make an informed choice.

An always-on webserver

Leitschuh’s research uncovered another behavior by Zoom for Mac that is also unsettling to security-conscious people. The app installs a webserver that accepts queries from other devices connected to the same local network. This server continues to run even when a Mac user uninstalls Zoom. Leitschuh showed how this webserver can be abused by people on the same network to force Macs to reinstall the app.

This clearly isn’t good. While the webserver is only accessible to devices on the same network, that still exposes people using untrusted networks. And if hackers were ever to come across a code-execution vulnerability in the webserver, the potential for abuse is even higher. Farley said Zoom introduced the webserver as a way to work around a change introduced in Safari 12 that requires users confirm with a click each time they want to start the Zoom app prior to joining a meeting.

“We feel that this is a legitimate solution to a poor user-experience problem, enabling our users to have faster, one-click-to-join meetings,” Farley wrote. “We are not alone among video-conferencing providers in implementing this solution.”

Independent security researcher Kevin Beaumont said on Twitter that the BlueJeans video conferencing app for Mac also opens a webserver.

Convenience is the enemy of security

As is the case with the auto-on webcam when joining meetings, Zoom’s implementation of a webserver is a convenience that comes at the potential cost of security. Neither behavior represents a critical vulnerability, but they do suggest Zoom developers could do more to lock down the Mac version of their app, particularly for users who may have less awareness of security issues.

And this is where precautions such as tape over a webcam come in. Users can never be sure developers have adequately safeguarded their apps against hacks or abuse, so the responsibility falls on end users to compensate. Other ways to protect against abuses of Zoom or other Web conference software is to use an app such as Little Snitch and configure it to give the conferencing software Internet access for only limited amounts of time. Another self-help protection is to configure macOS so that Zoom only has access to the webcam at specific times when it’s needed.

Yes, these additional protections can be a bother. But they also underscore the fundamental tension between convenience and security.