The Catch-22 that broke the Internet

Earlier this week, the Internet had a conniption. In broad patches around the globe, YouTube sputtered. Shopify stores shut down. Snapchat blinked out. And millions of people couldn’t access their Gmail accounts. The disruptions all stemmed from Google Cloud, which suffered a prolonged outage—an outage which also prevented Google engineers from pushing a fix. And so, for an entire afternoon and into the night, the Internet was stuck in a crippling ouroboros: Google couldn’t fix its cloud, because Google’s cloud was broken.

The root cause of the outage, as Google explained this week, was fairly unremarkable. (And no, it wasn’t hackers.) At 2:45pm ET on Sunday, the company initiated what should have been a routine configuration change, a maintenance event intended for a few servers in one geographic region. When that happens, Google routinely reroutes jobs those servers are running to other machines, like customers switching lines at Target when a register closes. Or sometimes, importantly, it just pauses those jobs until the maintenance is over.

What happened next gets technically complicated—a cascading combination of two misconfigurations and a software bug—but had a simple upshot. Rather than that small cluster of servers blinking out temporarily, Google’s automation software descheduled network control jobs in multiple locations. Think of the traffic running through Google’s cloud like cars approaching the Lincoln Tunnel. In that moment, its capacity effectively went from six tunnels to two. The result: Internet-wide gridlock.

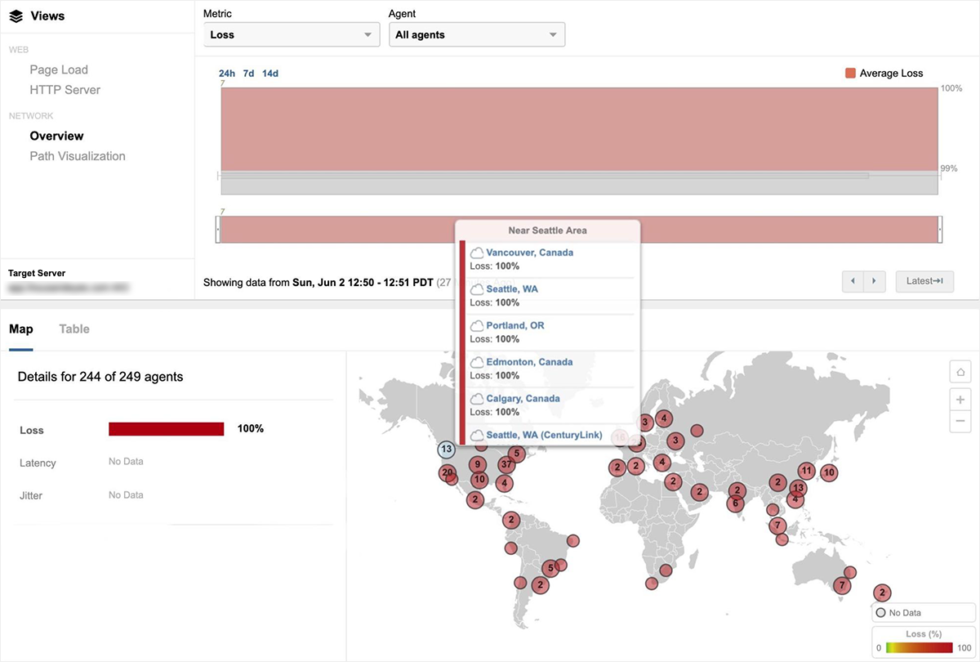

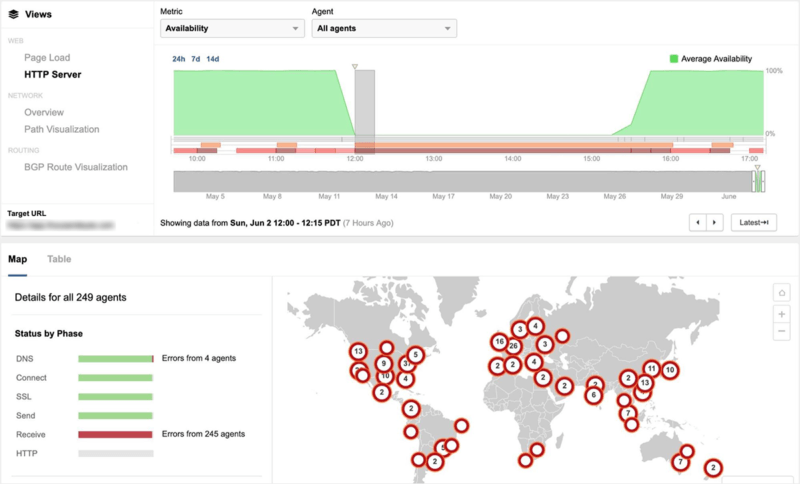

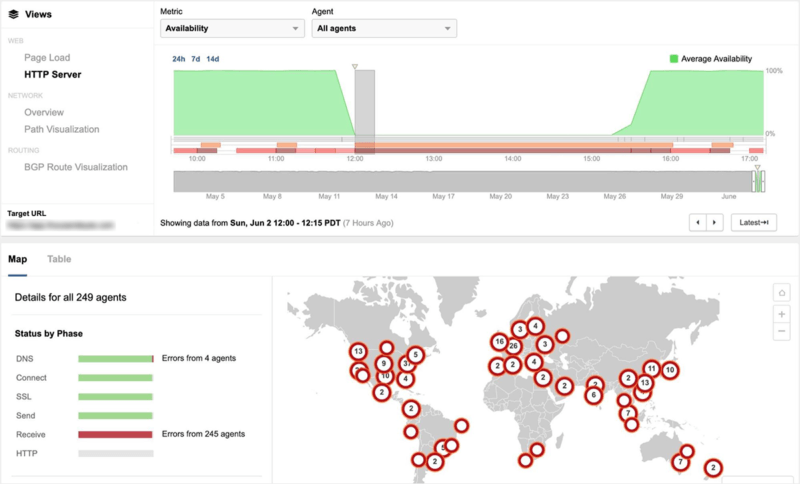

Still, even then, everything held steady for a couple minutes. Google’s network is designed to “fail static,” which means even after a control plane has been descheduled, it can function normally for a small period of time. It wasn’t long enough. By 2:47 pm ET, this happened:

Still, even then, everything held steady for a couple minutes. Google’s network is designed to “fail static,” which means even after a control plane has been descheduled, it can function normally for a small period of time. It wasn’t long enough. By 2:47 pm ET, this happened:

In moments like this, not all traffic fails equally. Google has automated systems in place to ensure that when it starts sinking, the lifeboats fill up in a specific order. “The network became congested, and our networking systems correctly triaged the traffic overload and dropped larger, less latency-sensitive traffic in order to preserve smaller latency-sensitive traffic flows,” wrote Google vice president of engineering Benjamin Treynor Sloss in an incident debrief, “much as urgent packages may be couriered by bicycle through even the worst traffic jam.” See? Lincoln Tunnel.

You can see how Google prioritized in the downtimes experienced by various services. According to Sloss, Google Cloud lost nearly a third of its traffic, which is why third parties like Shopify got nailed. YouTube lost 2.5 percent of views in a single hour. One percent of Gmail users ran into issues. And Google search skipped merrily along, at worst experiencing a barely perceptible slowdown in returning results.

“If I type in a search and it doesn’t respond right away, I’m going to Yahoo or something,” says Alex Henthorn-Iwane, vice president at digital experience monitoring company ThousandEyes. “So that was prioritized. It’s latency-sensitive, and it happens to be the cash cow. That’s not a surprising business decision to make on your network.”

But those decisions don’t only apply to the sites and services you saw flailing last week. In those moments, Google has to triage among not just user traffic but also the network’s control plane (which tells the network where to route traffic) and management traffic (which encompasses the sort of administrative tools that Google engineers would need to correct, say, a configuration problem that knocks a bunch of the internet offline).

“Management traffic, because it can be quite voluminous, you’re always careful. It’s a little bit scary to prioritize that, because it can eat up the network if something wrong happens with your management tools,” Henthorn-Iwane says. “It’s kind of a Catch-22 that happens with network management.”

Which is exactly what played out on Sunday. Google says its engineers were aware of the problem within two minutes. And yet! “Debugging the problem was significantly hampered by failure of tools competing over use of the now-congested network,” the company wrote in a detailed postmortem. “Furthermore, the scope and scale of the outage, and collateral damage to tooling as a result of network congestion, made it initially difficult to precisely identify impact and communicate accurately with customers.”

That “fog of war,” as Henthorn-Iwane calls it, meant that Google didn’t formulate a diagnosis until 6:01pm ET, well over three hours after the trouble began. Another hour later, at 7:03pm ET, it rolled out a new configuration to steady the ship. By 8:19pm ET, the network started to recover; at 9:10pm ET, it was back to business as usual.

Google has taken some steps to ensure that a similar network brownout doesn’t happen again. It took the automation software that deschedules jobs during maintenance offline, and the company says it won’t bring it back until “appropriate safeguards are in place” to prevent a global incident. It has also lengthened the amount of time its systems stay in “fail static” mode, which will give Google engineers more time to fix problems before customers feel the impact.

Still, it’s unclear whether Google, or any cloud provider, can avoid collapses like this entirely. Networks don’t have infinite capacity. They all make choices about what keeps working, and what doesn’t, in times of stress. And what’s remarkable about Google’s cloud outage isn’t the way the company prioritized, but that it has been so open and precise about what went wrong. Compare that to Facebook’s hours of downtime one day in March, which the company attributed to a “server configuration change that triggered a cascading series of issues,” full stop.

As always, take the latest cloud-based downtime as a reminder that much of what you experience as the Internet lives in servers owned by a handful of companies, and that companies are run by humans, and that humans make mistakes, some of which can ripple out much further than seems anything close to reasonable.

This story originally appeared on wired.com.