Supermicro hardware weaknesses let researchers backdoor an IBM cloud server

More than five years have passed since researchers warned of the serious security risks that a widely used administrative tool poses to servers used for some of the most sensitive and mission-critical computing. Now, new research shows how baseboard management controllers, as the embedded hardware is called, threaten premium cloud services from IBM and possibly other providers.

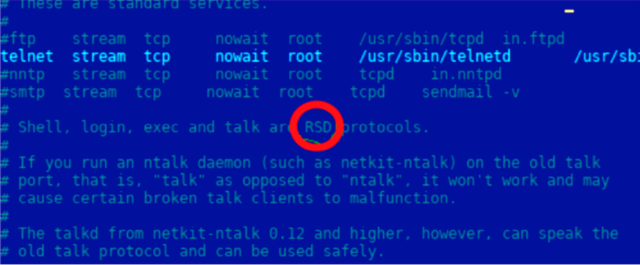

In short, BMCs are motherboard-attached microcontrollers that give extraordinary control over servers inside datacenters. Using the Intelligent Platform Management Interface, admins can reinstall operating systems, install or modify apps, and make configuration changes to large numbers of servers, without physically being on premises and, in many cases, without the servers being turned on. In 2013, researchers warned that BMCs that came preinstalled in servers from Dell, HP, and other name-brand manufacturers were so poorly secured that they gave attackers a stealthy and convenient way to take over entire fleets of servers inside datacenters.

Researchers at security firm Eclypsium on Tuesday plan to publish a paper about how BMC vulnerabilities threaten a premium cloud service provided by IBM and possibly other providers. The premium service is known as bare-metal cloud computing, an option offered to customers who want to store especially sensitive data but don’t want it to intermingle on the same servers other customers are using. The premium lets customers buy exclusive access to dedicated physical servers for as long as needed and, when the servers are no longer needed, return them to the cloud provider. The provider, in theory, wipes the servers clean so they can be safely used by another bare-metal customer.

Eclypsium’s research demonstrates that BMC vulnerabilities can undermine this model by allowing a customer to leave a backdoor that will remain active once the server is reassigned. The backdoor leaves the customer open to a variety of attacks, including data theft, denial of service, and ransomware.

To prove their point, the researchers commissioned a bare-metal server from IBM’s SoftLayer cloud service. The server was using a BMC from Supermicro, a hardware manufacturer with a wide range of known firmware vulnerabilities. The researchers confirmed the BMC was running the latest firmware, recorded the chassis and product serial numbers, and then made a slight modification to the BMC firmware in the form of a single bitflip inside a comment. The researchers also created an additional user account in the BMC’s Intelligent Platform Management Interface.

The researchers then returned the server to IBM and requested new ones. Eventually, the researchers were assigned one with the same chassis and product serial number as the server they had previously obtained and modified. An inspection of the server didn’t inspire confidence. According to the report:

We did notice that the additional IPMI user was removed by the reclamation process, however the BMC firmware containing the flipped bit was still present. This indicated that the servers’ BMC firmware was not re-flashed during the server reclamation process. The combination of using vulnerable hardware and not re-flashing the firmware makes it possible for a malicious party to implant the server’s BMC code and inflict damage or steal data from IBM clients that use that server in the future.

We also noticed that BMC logs were retained across provisioning, and BMC root password remained the same across provisioning. By not deleting the logs, a new customer could gain insight into the actions and behaviors of the previous owner of the device, while knowing the BMC root password could enable an attacker to more easily gain control over the machine in the future.

Not the first time

Eclysium researchers aren’t the only ones to document how weaknesses in Supermicro BMCs can put bare-metal cloud users at risk. In 2012, researchers at security firm Rapid7 discovered that the Supermicro controllers were vulnerable to hacks transmitted over a computer’s universal plug and play networking protocols that gave attackers unfettered access. They went on to combine those insights with new findings from researcher Dan Farmer that showed how to build extremely hard-to-detect backdoors in the BMCs.

To the chagrin of the researchers, they found the exploits continued to work against bare-metal servers despite new measures cloud providers introduced in an attempt to mitigate the vulnerability. HD Moore—who at the time was Rapid7’s chief research officer and is now vice president of research and development at Atredis Partners—said an IPMI feature known as a keyboard controller style made backdooring the BMC of bare-metal servers impossible. As was the case with IBM SoftLayer, a different cloud provider failed to detect and re-flash modified firmware.

“It is ridiculously dangerous to use a dedicated (bare-metal) server if the BMC is enabled,” Moore said in an interview. “There is no guarantee that the BMC hasn’t been backdoored before your server was provisioned. The high-end cloud providers have hardware solutions to defend against these attacks, but anyone using stock supermicro boards is going to be at risk.”

In a longer message to Ars, Moore provided more details around his research in 2012 and 2013:

While investigating the impact of the libupnp vulnerabilities in late 2012, we determined that Super Micro BMCs were affected and wrote a Metasploit module to gain remote root shells on those devices via that vector. Shortly after, in 2013, Dan Farmer released his research into IPMI, and we continued looking at the exposure created by Super Micro BMCs, with an eye towards the ability of both a host and a BMC to subvert each other. The process was covered in a blog post and we continued looking into Super Micro BMC issues in general.

One scenario we looked at was whether dedicated server providers (what we call bare-metal cloud today) adequately protected the BMC interfaces and whether an attack on a rented server could result in permanent access to that hardware. We determined that this was possible and that there weren’t any great solutions to it, but we only had a few ISPs as data points. Starting in 2013, we saw major changes to how dedicated server providers protected and isolated the BMC interfaces, but it wasn’t enough to prevent a permanent backdoor from being introduced by an attacker.

Dedicated server providers responded to the public vulnerabilities in IPMI and libupnp by putting the BMC network interfaces behind firewalls and changing the admin passwords on the BMCs so that a casual user of the rented server couldn’t interface with it. This didn’t prevent access to the BMC, as the IPMI over KCS channel allows a new admin user to be created and in the case of Super Micro at least, the firmware to be re-flashed. We verified that we could re-flash a dedicated server with an older version of the firmware and then exploit it using the libupnp vulnerability.

This resulted in read access to the nvram of the BMC and a root shell in the BMC’s Linux-based OS. The nvram contained the plaintext passwords, which were shared across all servers at that particular provider. We noticed that the BMC could access BMCs connected to other customer’s servers via the dedicated network, and that the firmware could be modified so that future updates would not apply. Creating a malicious firmware image for Super Micro BMCs is trivial using public tools (https://github.com/devicenull/ipmi_firmware_tools).

We didn’t publish those results, but it led to more due diligence on our part when choosing dedicated servers for our own use, and quite a few conversations with Zach Wikholm at Cari.net, who was juggling related issues in their data center, including active exploitation of Super Micro BMC vulnerabilities.

In a statement, IBM officials wrote:

We are not aware of any client or IBM data being put at risk because of this reported potential vulnerability, and we have taken actions to eliminate the vulnerability. Given the remediation steps we have taken and the level of difficulty required to exploit this vulnerability, we believe the potential impact to clients is low. While the report focuses on IBM, this was actually a potential industry-wide vulnerability for all cloud service providers, and we thank Eclypsium for bringing it to the attention of the industry.

In a blog post published Monday, IBM officials said the countermeasures include “forcing all BMCs, including those that are already reporting up-to-date firmware, to be re-flashed with factory firmware before they are re-provisioned to other customers. All logs in the BMC firmware are erased and all passwords to the BMC firmware are regenerated.”

Moore, for his part, remained unconvinced the measure will adequately protect against the BMC hacks because, he said, “software-based re-flashing tools can be subverted by an attacker that has already flashed a malicious image. I don’t think IBM can solve it short of physically disabling the BMC via a motherboard jumper.”