Supermicro boards were so bug ridden, why would hackers ever need implants?

By now, everyone knows the premise behind two unconfirmed Bloomberg articles that have dominated security headlines over the past week: spies from China got multiple factories to sneak data-stealing hardware into Supermicro motherboards before the servers that used them were shipped to Apple, Amazon, an unnamed major US telecommunications provider, and more than two dozen other unnamed companies.

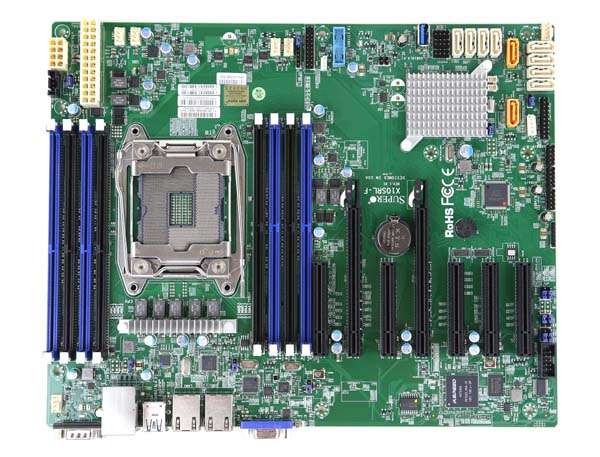

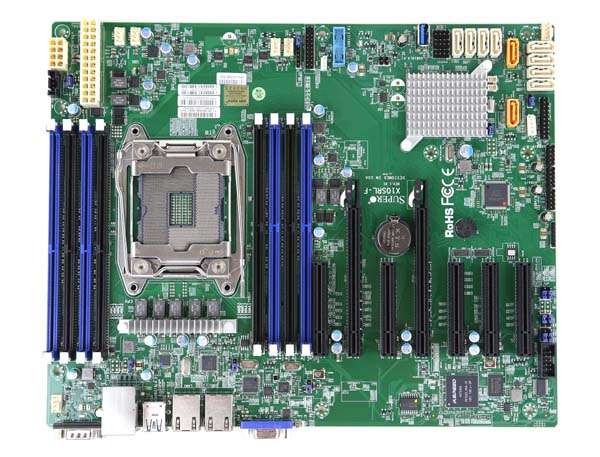

Motherboards that wound up inside the networks of Apple, Amazon, and more than two dozen unnamed companies reportedly included a chip no bigger than a grain of rice that funneled instructions to the baseboard management controller, a motherboard component that allows administrators to monitor or control large fleets of servers, even when they’re turned off or corrupted. The rogue instructions, Bloomberg reported, caused the BMCs to download malicious code from attacker-controlled computers and have it executed by the server’s operating system.

Motherboards that Bloomberg said were discovered inside a major US telecom had an implant built into their Ethernet connector that established a “covert staging area within sensitive networks.” Citing Yossi Appleboum, a co-CEO of security company reportedly hired to scan the unnamed telecom’s network for suspicious devices, Bloomberg said the rogue hardware was implanted at the time the server was being assembled at a Supermicro subcontractor factory in Guangzhou. Like the tiny chip reportedly controlling the BMC in Apple and Amazon servers, Bloomberg said the Ethernet manipulation was “designed to give attackers invisible access to data on a computer network.”

Like unicorns jumping over rainbows

The complexity, sophistication, and surgical precision needed to pull off such attacks as reported are breathtaking, particularly at the reported scale. First, there’s the considerable logistics capability required to seed supply chains starting in China in a way the ensures backdoored equipment ships to specific US targets but not so widely to become discovered. Bloomberg acknowledged the skill and sheer luck of success by comparing the feat to “throwing a stick in the Yangtze River upstream from Shanghai and ensuring that it washes ashore in Seattle.” The news service also quotes hardware hacking expert Joe Grand comparing it to “witnessing a unicorn jumping over a rainbow.”

By Bloomberg’s account, the attacks involved people posing as representatives of Supermicro or the Chinese government approaching the managers of at least four subcontractor factories that built Supermicro motherboards. The representatives would offer bribes in exchange for the managers making changes to the boards’ official designs. If bribes didn’t work, the representatives threatened managers with inspections that could shut down the factories. Eventually, Bloomberg said, the factory managers agreed to modify the board designs to add malicious hardware that was nearly invisible to the naked eye.

The articles don’t explain how attackers ensured the altered equipment shipped broadly enough to reach intended targets in a distant country without also going to other unintended companies. Nation-state hackers almost always endeavor to distribute their custom spyware as narrowly as possible to only chosen high-value targets, lest the spy tools spread widely and become discovered the way the Stuxnet worm that targeted Iran’s nuclear program became public when its creators lost control of it.

In search of low-hanging fruit

The other monumental effort required by the reported supply-chain attacks is the vast amount of engineering and reverse engineering. Based on Bloomberg’s descriptions, the attacks involved designing at least two custom implants (one that was no bigger than a grain of rice), modifying the motherboards to work with the custom implants, and ensuring the modified boards would work even when administrators installed new firmware on the boards. While the requirements are within the means of a determined nation, three hardware security experts interviewed for this story said the factory-seeded hardware implants are unnecessarily complex and cumbersome, particularly at the reported scale, which involved almost 30 targets.

“Attackers tend to prefer the lowest-hanging fruit that gets them the best access for the longest period of time,” Steve Lord, a researcher specializing in hardware hacking and co-founder of UK conference 44CON, told me. “Hardware attacks could provide very long lifetimes but are very high up the tree in terms of cost to implement.”

He continued:

Once discovered, such an attack would be burned for every affected board as people would replace them. Additionally, such a backdoor would have to be very carefully designed to work regardless of future (legit) system firmware upgrades, as the implant could cause damage to a system, which in turn would lead to a loss of capability and possible discovery.

The analysis voiced by the researchers interviewed by this post isn’t the only skepticism coming from well-placed sources. On Wednesday, senior NSA advisor Rob Joyce reportedly joined the chorus of government officials who said they had no information to corroborate any of the claims in the Bloomberg articles.

“What I can’t find are any ties to the claims that are in the article,” Joyce said, according to this article from Cyberscoop. “I have pretty great access, [and yet] I don’t have a lead to pull from the government side. We’re just befuddled.” He reportedly added: “I have grave concerns about where this has taken us. I worry that we’re chasing shadows right now.”

Bloomberg representatives didn’t respond to a request for comment for this post. At the time this post went live, both Bloomberg articles remained online.

An easier way

Lord was one of several researchers who unearthed a variety of serious vulnerabilities and weaknesses in Supermicro motherboard firmware (PDF) in 2013 and 2014. This time frame closely aligns with the 2014 to 2015 hardware attacks Bloomberg reported. Chief among the Supermicro weaknesses, the firmware update process didn’t use digital signing to ensure only authorized versions were installed. The failure to offer such a basic safeguard would have made it easy for attackers to install malicious firmware on Supermicro motherboards that would have done the same things Bloomberg says the hardware implants did.

Also in 2013, a team of academic researchers published a scathing critique of Supermicro security (PDF). The paper said the “textbook vulnerabilities” the researchers found in BMC firmware used in Supermicro motherboards “suggest either incompetence or indifference towards customers’ security.” The critical flaws included a buffer overflow in the boards’ Web interface that gave attackers unfettered root access to the server and a binary file that stored administrator passwords in plaintext.

HD Moore—who in 2013 was chief research officer of security firm Rapid7 and chief architect of the Metasploit project used by penetration testers and hackers—was among the researchers who also reported a raft of vulnerabilities. That included a stack buffer overflow, the clear-text password disclosure bug, and a way attackers could bypass authentication requirements to take control of the BMC. Moore is now vice president of research and development at Atredis Partners.

Any one of these flaws, Moore said this week, could have been exploited to install malicious, custom-made firmware on an exposed Supermicro motherboard. Ars covered these vulnerabilities here.

“I spoke with Jordan a few months ago,” Moore said, referring to Jordan Robertson, one of two reporters whose names appears on the Bloomberg articles. “We chatted about a bunch of things, but I pushed back on the idea that it would be practical to backdoor Supermicro BMCs with hardware, as it is still trivial to do so in software. It would be really silly for someone to add a chip when even a non-subtle change to the flashed firmware would be sufficient.”

Over the years, Supermicro issued updates that patched some of the vulnerabilities reported in 2013, but a year later researchers issued an advisory that said that nearly 32,000 servers continued to expose passwords and that the binary files on those machines were trivial to download. More concerning still, this post from security firm Eclypsium shows that, as of last month, cryptographically signed firmware updates for Supermicro motherboards were still not publicly available. That means that, for the past five years, it was trivial for people with physical access to the boards to flash them with custom firmware that has the same capabilities as the hardware implants reported by Bloomberg.

Discretion assured/easier to seed

The software modifications made possible by exploiting these or similar weaknesses arguably would have been harder to detect than the hardware additions reported by Bloomberg. Moore said the only way to identify a Supermicro board with malicious BMC firmware would be to go through the time-consuming process of physically dumping the image, comparing it to a known good version, and examining the setup options for booting the firmware.

Modified Supermicro firmware, he said, can pretend to accept firmware updates but instead extract the version number and falsely show it the next time it boots. The malicious image could also avoid detection by responding with a non-modified image if a dump is requested through the normal Supermicro interface.

According to documents leaked by former NSA subcontractor Edward Snowden, the use of custom firmware was the method employees with the agency’s Tailored Access Operations unit used to backdoor Cisco networking gear before it shipped to targets of interest.

Besides requiring considerably less engineering muscle than hardware implants, backdoored firmware would arguably be easier to seed into the supply chain. The manipulations could happen in the factory, either by compromising the plants’ computers or gaining the cooperation of one or more employees or by intercepting boards during shipping the way the NSA did with the Cisco gear they backdoored.

Either way, attackers wouldn’t need the help of factory managers, and if the firmware was changed during shipping, that would make it easier to ensure the modified hardware reached only intended targets, rather than risking collateral damage on other companies.

Of course, the easier path of backdooring motherboards with firmware in no way disproves the Bloomberg claims of hardware implants. It’s possible the attackers were testing a new proof-of-concept and wanted to show off their capabilities to the world. Or maybe they had other reasons to choose a more costly and difficult backdoor method. But those possibilities seem far fetched.

“I believe the backdoor described [by Bloomberg] is technically possible. I don’t think it’s plausible,” said Joe FitzPatrick, a security expert and founder of Hardware Security Resources who was quoted by Bloomberg. “There are so many far easier ways to do the same job. It makes no sense—from a capability, cost, complexity, reliability, repudiability perspective—to do it as described in the article.”