Strange snafu misroutes domestic US Internet traffic through China Telecom

China Telecom, the large international communications carrier with close ties to the Chinese government, misdirected big chunks of Internet traffic through a roundabout path that threatened the security and integrity of data passing between various providers’ backbones for two-and-a-half years, a security expert said Monday. It remained unclear if the highly circuitous paths were intentional hijackings of the Internet’s Border Gateway Protocol or were caused by accidental mishandlings.

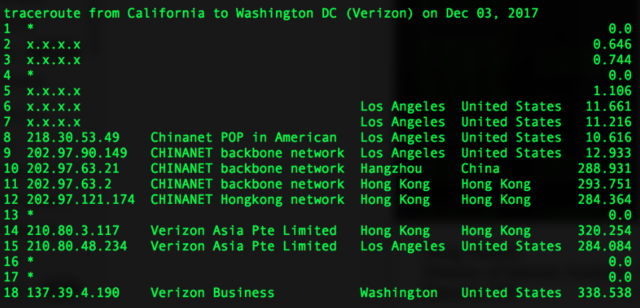

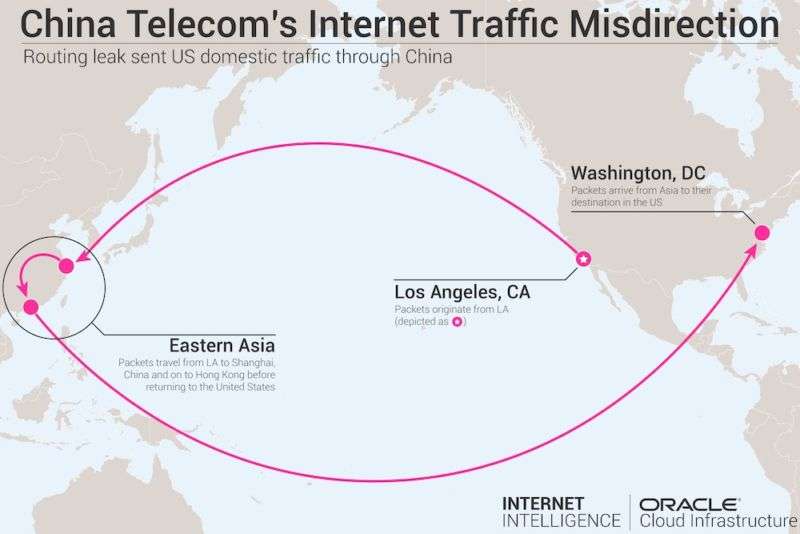

For almost a week late last year, the improper routing caused some US domestic Internet communications to be diverted to mainland China before reaching their intended destination, Doug Madory, a researcher specializing in the security of the Internet’s global BGP routing system, told Ars. As the following traceroute from December 3, 2017 shows, traffic originating in Los Angeles first passed through a China Telecom facility in Hangzhou, China, before reaching its final stop in Washington DC. The problematic route, which is visualized in the graphic above, was the result of China Telecom inserting itself into the inbound path of Verizon Asian Pacific.

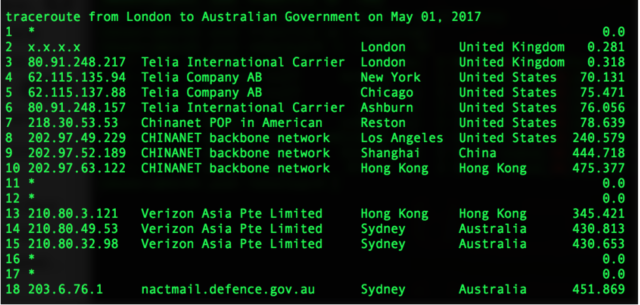

The routing snafu involving domestic US Internet traffic coincided with a larger misdirection that started in late 2015 and lasted for about two-and-a-half years, Madory said in a blog post published Monday. The misdirection was the result of AS4134, the autonomous system belonging to China Telecom, incorrectly handling the routing announcements of AS703, Verizon’s Asia Pacific AS. The mishandled routing announcements caused several international carriers—including Telia’s AS1299, Tata’s AS6453, GTT’s AS3257, and Vodafone’s AS1273—to send data destined for Verizon Asia Pacific through China Telecom, rather than using the normal multinational telecoms.

For the next 30 months or so, a large amount of traffic that used Verizon’s AS703 improperly passed through AS4134 in mainland China first. The circuitous route is reflected in the following traceroute taken on May 1, 2017:

“On average I believe we saw as much as 20 percent of our BGP sources carrying these routes at any given time,” Madory told Ars. “It isn’t the same as saying 20 percent of the internet, but it is safe to say that a significant minority of the internet was carrying these routes.”

BGP fragility

The sustained misdirection further underscores the fragility of BGP, which forms the underpinning of the Internet’s global routing system. In April, unknown attackers used BGP hijacking to redirect traffic destined for Amazon’s Route 53 domain-resolution service. The two-hour event allowed the attackers to steal about $150,000 in digital coins as unwitting people were routed to a fake MyEtherWallet.com site rather than the authentic wallet service that got called normally. When end users clicked through a messages warning of a self-signed certificate, the fake site drained their digital wallets. In 2013, malicious hackers repeatedly hijacked massive chucks of Internet traffic in what was likely a test run. Also in 2013, spyware service provider Hacking Team orchestrated the hijacking of IP addresses it didn’t own to help Italian police regain control over several computers they were monitoring in an investigation. A year later, domestic Russian Internet traffic was diverted through China.

On two occasions last year, traffic to and from major US companies was suspiciously and intentionally routed through Russian service providers. Traffic for Visa, MasterCard, and Symantec—among others—was rerouted in the first incident in April, while Google, Facebook, Apple, and Microsoft traffic was affected in a separate BGP event about eight months later.

By routing traffic through networks controlled by the attacker, BGP manipulation allows the adversary to monitor, corrupt, or modify any data that’s not encrypted. Even when data is encrypted, attacks with names such as DROWN or Logjam have raised the specter some of the encrypted data may have been decrypted. Even when encryption can’t be defeated, attackers can sometimes trick targets into dropping their defenses, as the BGP hijacking against MyEtherWallet.com did.

Madory said the improper routing he reported finally stopped after he “expended a great deal of effort to stop it in 2017.” His report on Monday went on to endorse a proposed standard known as RPKI-based AS path verification. The mechanism, had it been deployed, would have stopped some of the events Madory documented, he said.

Neither China Telecom nor Verizon responded to an email seeking comment for this post.

Monday’s blog post comes two weeks after researchers at the US Naval War College and Tel Aviv University published a report that quickly got the attention of BGP security professionals. Titled China’s Maxim–Leave No Access Point Unexploited: The Hidden Story of China Telecom’s BGP Hijacking, it claimed the Chinese government has brazenly used China Telecom for years to to divert huge amounts of traffic to China-controlled networks before it’s ultimately delivered to its final destination. The report named four specific routes—Canada to South Korea, US to Italy, Scandinavia to Japan, and Italy to Thailand—that were reportedly manipulated between 2015 and 2017 as a result of BGP activities of China Telecom.

“While one may argue such attacks can always be explained by ‘normal’ BGP behavior, these, in particular, suggest malicious intent, precisely because of their unusual transit characteristics—namely the lengthened routes and the abnormal durations,” the authors wrote. The Canada to South Korea leak, the report said, lasted for about six months and started in February 2016. The remaining three reported hijackings took place in 2017, with two of them reportedly lasting for months and the third taking place over about nine hours.

Definitely concerning

The report was unusual in that it didn’t provide AS numbers, specific dates and other specifics that allowed other researchers to confirm the claims. Ars and other researchers asked the authors to make the data available, and they responded with a small amount of traceroute data. Madory said the Scandinavia-to-Japan event reported in the paper two weeks ago was actually a small part of the two-and-a-half-year misdirection he reported Monday.

“We are describing the same thing in different ways,” he told Ars, speaking of the two-and-a-half-year event he documented and the two-month hijacking reported two weeks ago. “They may have only known about it for those two months in 2017, but I can guarantee you that it was going for much longer.”

Madory said he was unable to confirm the three other hijackings the authors report. His report on Monday, however, leaves little doubt that China Telecom has either knowingly or otherwise engaged in BGP leaks that have affected large chunks of Internet traffic for a sustained period.

The domestic US traffic, in particular, “becomes an even more extreme example,” he told Ars. “When it gets to US-to-US traffic traveling through mainland China, it becomes a question of is this a malicious incident or is it accidental? It’s definitely concerning. I think people will be surprised to see that US-to-US traffic was sent through China Telecom for days.”