In new gaffe, Facebook improperly collects email contacts for 1.5 million

Facebook’s privacy gaffes keep coming. On Wednesday, the social media company said it collected the stored email address lists of as many as 1.5 million users without permission. On Thursday, the company said the number of Instagram users affected by a previously reported password storage error was in the “millions,” not the “tens of thousands” as previously estimated.

Facebook said the email contact collection was the result of a highly flawed verification technique that instructed some users to supply the password for the email address associated with their account if they wanted to continue using Facebook. Security experts almost unanimously criticized the practice, and Facebook dropped it as soon as it was reported.

In a statement issued to reporters, Facebook wrote:

Earlier this month we stopped offering email password verification as an option for people verifying their account when signing up for Facebook for the first time. When we looked into the steps people were going through to verify their accounts we found that in some cases people’s email contacts were also unintentionally uploaded to Facebook when they created their account. We estimate that up to 1.5 million people’s email contacts may have been uploaded. These contacts were not shared with anyone and we’re deleting them. We’ve fixed the underlying issue and are notifying people whose contacts were imported. People can also review and manage the contacts they share with Facebook in their settings.

Business Insider first reported the harvesting of the email contacts. When users gave their passwords to Facebook, the publication said, they received a message declaring that Facebook was importing their contacts. The collection happened without asking for permission first.

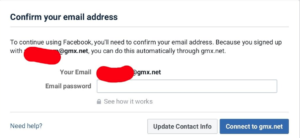

While Facebook’s statement referred to the email verification step as an “option,” the language displayed in a tweeted screenshot of the message (right) told users: “To continue using Facebook, you’ll need to confirm your email address.” Many users, it seems, could be forgiven if they thought supplying their password was a condition of using the social media site. A Facebook representative told Ars that these users could also have confirmed their accounts with a code sent to their phone or a link sent to their email had they clicked the “need help” button in the pop-up window.

Hashing it out

Facebook has said it didn’t store the passwords, but in yet another Facebook privacy blunder disclosed last month, the company confirmed that it improperly stored hundreds of millions of user passwords in plain text rather than as cryptographic hashes. Hashes are long strings of random-looking text that are generated by passing a password, message, or file through an algorithm. Because hashes can’t be cryptographically reversed, security experts say they are the only secure way to store them.

In late March, Facebook said the plaintext password error affected hundreds of millions of Facebook Lite users, tens of millions of other Facebook users, and tens of thousands of Instagram users. The Facebook disclosure was updated on Thursday to say the number of affected Instagram accounts was much higher.

“Since this post was published, we discovered additional logs of Instagram passwords being stored in a readable format,” Thursday’s update said. “We now estimate that this issue impacted millions of Instagram users. We will be notifying these users as we did the others. Our investigation has determined that these stored passwords were not internally abused or improperly accessed.”

Facebook has been buffeted by a series of privacy gaffes since January 2018. That’s when a New York Times expose revealed that political firm Cambridge Analytica improperly harvested tens of millions of Facebook users’ data. Two months later, reporting showed that the social media site collected metadata from years’ worth of calls and texts users made or sent with Android phones.

Last month, CEO Mark Zuckerberg said he planned to rebrand the site he founded as a privacy service.