How a turf war and a botched contract landed 2 pentesters in Iowa jail

In the early hours of September 11, a dispatcher with the sheriff’s department in Dallas County, Iowa, spotted something alarming on a surveillance camera in the county courthouse. Two men who had tripped an alarm after popping open a locked door were wandering through courtrooms on the third floor, she reported over the radio as deputies raced to the scene. The intruders wore backpacks and were crouching down next to judges’ benches. When the first deputy pulled into the parking lot, the men moved to an open area outside the court rooms and concealed themselves.

“They were crouched down like turkeys peeking over the balcony,” Dallas County Sheriff Chad Leonard said in an interview. “Here we are at 12:30 in the morning confronted with this issue—on September 11, no less. We have two unknown people in our courthouse—in a government building—carrying backpacks that remind me and several other deputies of maybe the pressure cooker bombs.”

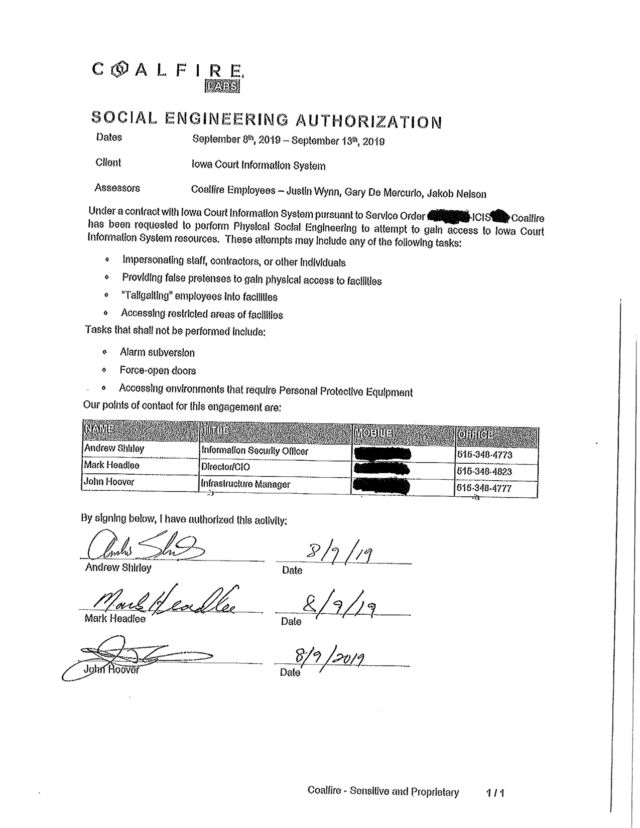

After more deputies arrived, Justin Wynn, 29 of Naples, Florida, and Gary De Mercurio, 43 of Seattle, slowly proceeded down the stairs with hands raised. They then presented the deputies with a letter that explained the intruders weren’t criminals but rather penetration testers who had been hired by Iowa’s State Court Administration to test the security of its court information system. After calling one or more of the state court officials listed in the letter, the deputies were satisfied the men were authorized to be in the building.

The deputies listened with interest as the pentesters—who work for Westminster, Colorado-based Coalfire Labs—explained how they got in. They said they found a courthouse door unlocked. So they closed it from the outside and let it lock. Then they slipped a plastic cutting board through a crack in the door and manipulated its locking mechanism. (Pentesters frequently use makeshift or self-created tools in their craft to flip latches, trigger motion-detected mechanisms, and test other security systems.) The deputies seemed impressed.

When Leonard arrived on the scene, the mood quickly changed. Leonard read the letter and sized the men up. It said the men were authorized to perform “physical social engineering to attempt to gain access” to courthouse systems. The attempts could include:

- Impersonating staff, contractors, or other individuals

- Providing false pretenses to gain physical access to facilities

- “Tailgating” employees into facilities

- Accessing restricted areas of facilities

The letter also listed tasks that should not be performed, including:

- Alarm subversion

- Force-open doors

- Accessing environments that require personal protective equipment

The pentesters had already said they used a tool to open the front door. Leonard took that to mean the men had violated the restriction against forcing doors open. Leonard also said the men attempted to turn off the alarm—something Coalfire officials vehemently deny. In Leonard’s mind that was a second violation. Another reason for doubt: one of the people listed as a contact on the get-out-of-jail-free letter didn’t answer the deputies’ calls, while another said he didn’t believe the men had permission to conduct physical intrusions.

The sheriff also said he and his deputies smelled alcohol on the breath of one of the men. (Leonard, who didn’t identify which Coalfire employee it was, said a test later showed the pentester had a blood alcohol content of 0.05, the equivalent of one or two drinks. It is below the 0.08 threshold for an operating while intoxicated conviction.)

Leonard promptly had the men arrested on felony third-degree burglary charges. They spent the night in jail in separate cells, where one of them was given a bench with a sleeping pad. After being arraigned the following morning, they were shocked when they were once again returned to jail. The pentesters weren’t released until late that afternoon or early that evening on $100,000 bail ($50,000 for each).

The charges have since been reduced to misdemeanor trespassing charges. Trial is scheduled for April. Meanwhile, the sheriff’s department in nearby Polk County is conducting a criminal investigation into a September 10 break-in on its courthouse under the same arrangement with the State Judicial Administration.

Cause célèbre

The case has become a cause célèbre that has galvanized a variety of different interests. For Coalfire and professional pentesters around the world, the charges are an affront that threatens their ability to carry out what has long been considered a key practice in ensuring clients’ systems are truly secure. If pentesters can’t be confident that physical assessments won’t result in criminal prosecutions, security professionals say they’ll no longer be able to carry out this core function with the vigor and thoroughness it requires.

“This does affect my job directly,” said a penetration tester who asked to be identified only by his handle Tinker, or @TinkerSec on Twitter. “This affects physical pentesting in general and it really affects government pentesting when the state government can’t provide protection and you can’t trust the state government to stand behind its own laws.”

For Dallas County officials, on the other hand—and possibly officials in nearby Polk County—the case is about their sovereign right to police their tax-payer-owned facilities. Leonard said that Iowa’s State Court Administration, or SCA, didn’t have the legal authority to permit the men to force their way into the county-owned building.

What’s more, the sheriff said the pentesters’ use of lock-picking gear and their alleged tampering with an alarm system—again, Coalfire disputes the latter claim—violated the terms of the get-out-of-jail-free letter. The sheriff also said the midnight assessment was a violation of a term spelled out in one section of the rules of engagement document. It said pentesting was to be conducted between 6AM and 6PM Mountain time. (Curiously, Iowa is in the Central time zone. Another term of the same rules of engagement (pdf) said physical testing “Can be during the day and evening.” Leonard wasn’t aware of this last detail until I pointed it out in the interview. The sheriff has declined to release video of the incident.)

You’re going to jail

The get-out-of-jail-free letter “said you won’t manipulate doors,” Leonard said. “Well, they picked four doors. It said they won’t manipulate the alarm system. They went right up to the alarm and tried to shut it off. The biggest issue is they were only supposed to work from 6AM to 6PM. They came out in the middle of the night and broke in.”

Equally important, Leonard said, is what he believed to be the overstepping of Iowa officials who retained Coalfire. When the sheriff confronted the men that night, he said: “The State of Iowa has no authority to allow you to break into a county building. You’re going to jail.”

No one has more stake in the controversy than Wynn and De Mercurio, who risk being convicted of criminal charges that among other things could jeopardize government clearances and future job prospects. Coalfire CEO Tom McAndrew said in a statement last month that Leonard “failed to exercise commonsense and good judgement and turned this engagement into a political battle between the State and the County.” McAndrew also noted that Coalfire conducted an engagement for Iowa’s SCA in 2015 without incident.

Leonard said he has been receiving “hate mail” from as far away as Europe ever since the incident two months ago.

McAndrew told me that Wynn and De Mercurio did everything by the book. The employees, McAndrew said, intentionally tripped the alarm and then proceeded to the third floor to test the response. Crouching on floors or otherwise trying to be covert is standard practice after alarms are tripped to further test authorities’ response and see what surveillance cameras can detect.