Hack in the box: Hacking into companies with “warshipping”

LAS VEGAS—Penetration testers have long gone to great lengths to demonstrate the potential chinks in their clients’ networks before less friendly attackers exploit them. But in recent tests by IBM’s X-Force Red, the penetration testers never had to leave home to get in the door at targeted sites, and the targets weren’t aware they were exposed until they got the bad news in report form. That’s because the people at X-Force Red put a new spin on sneaking in—something they’ve dubbed “warshipping.”

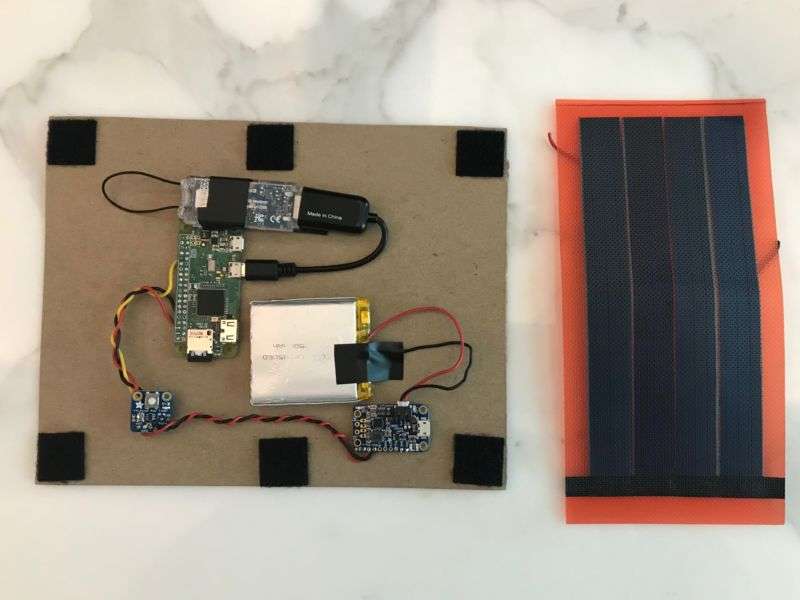

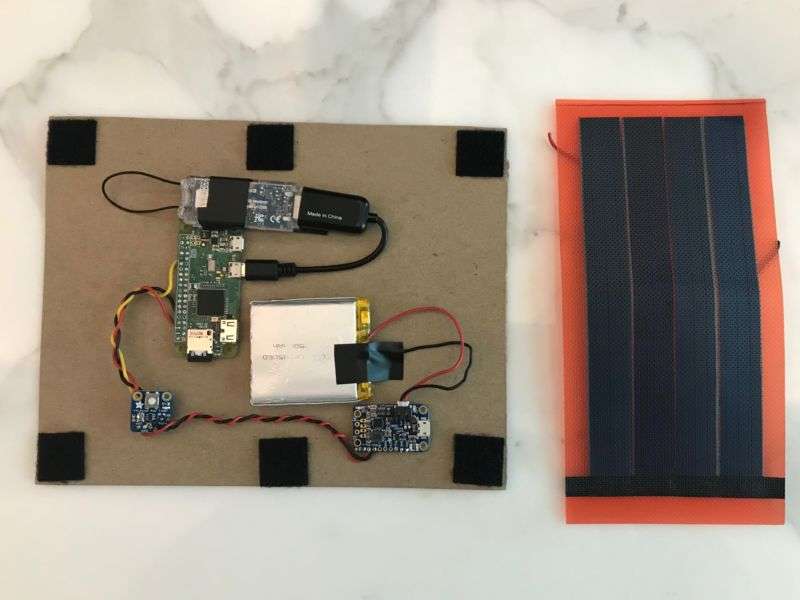

Using less than $100 worth of gear—including a Raspberry Pi Zero W, a small battery, and a cellular modem—the X-Force Red team assembled a mobile attack platform that fit neatly within a cardboard spacer dropped into a shipping box or embedded in objects such as a stuffed animal or plaque. At the Black Hat security conference here last week, Ars got a close look at the hardware that has weaponized cardboard.

We’ve looked at such devices, typically referred to as “drop boxes,” before. Ars even used one in our passive surveillance of an NPR reporter, capturing his network traffic and routing a dump of his packets across the country for us to sift through. Covert drop boxes (once a specialty of Pwnie Express) have taken the form of “wall wart” device chargers, Wi-Fi routers, and even power strips. And mobile devices have also been brought to play, allowing “war walking”—attacks launched remotely as a device concealed in a bag, suitcase, or backpack is carried nonchalantly into a bank, corporate lobby, or other targeted location.

But unless you’re trying to get your daily steps in, IBM X-Force Red Global Managing Partner and Head Charles Henderson told Ars that you can just let a shipping company do the work for you. “There have been people that have shipped cell phones, things like that,” Henderson noted. “The thing that’s cool about this is, this is the wall of the box. It can be easily built into the cardboard. If you get a phone shipped to you, you’re suspicious of it. If you get a box or maybe a plaque that says you’re the new [chief information security officer] of the year, you might not.”

The plaque might just go right up on the wall. “Put a $13 solar charger panel on the plaque, and that makes it a permanent fixture in a CISO’s office… a $13 panel that, and actually, by the time it discharges the battery, between times when we check in, that can charge it back up. So technically you could do pretty much infinite, up to the life of the battery, if you set that in the right place.”

The hardware has also been planted in a stuffed animal and even inside the case of a normal Wi-Fi router.

Signals everywhere

The near-ubiquity of some kind of cellular signal and the advent of Internet of Things (IoT) cellular modems—frequently used by freight carriers to track trailers and by other remote, low-power devices—has also created a new set of security concerns for companies and individuals targeted for industrial espionage and other criminal activity.

Henderson emphasizes that in each case, his team had permission from someone with authority at each company that received a “warship.” But the companies weren’t widely warned about what was coming. “When we talked to the CSO or the CFO and got permission, we said, ‘OK, don’t tell anybody.'” And with the exception of one shipment—which failed mostly because of rough handling—every one of the cardboard Trojan horses was welcomed with open arms.

Express hack delivery

One “warshipping” box sent out by Henderson’s team found its way into a company’s secure research center—a place where cell phones are banned. The rig, capable of storing data on an SD card until it regains a cell connection, was able to perform reconnaissance inside the facility before dumping it back to home when the box was disposed of.

“It went where they have RF shielding, where no package like this should go,” Henderson said. “After opening it and basically determining that it was benign in their opinion, they took it in. Obviously, if you had shipped a computer with a battery attached to it, an external battery and some sort of GPS, no one’s going to do that—even with a phone, they aren’t going to do it. They have guidelines that say, ‘You are not allowed to bring a phone into these facilities.'” But because the warshipping rig was concealed within the cardboard of the box itself, it was given unfettered access.

All of this is well within the grasp of many attackers. “It’s off-the-shelf components,” said Steve Ocepek, X-Force Red’s Hacking CTO, as he showed me the warshipping rig. “If we were to show you a board that we fabbed in a plant, it wouldn’t be that interesting, right? This is a battery you can get off of Adafruit or wherever.” The most expensive component of the rig is the cellular modem.

Because of the “maker” movement, he said, “we’ve crossed into this weird area because you can put this together for under $100. I mean, the [Raspberry Pi] Zero W, that’s five bucks, right? So it’s crazy.”

The components also include a few other Adafruit components: a PowerBoost 500 charger component that boosts the battery output up to 5 volts, and a timer board to help manage power—extending the life of the rig by limiting it to periodic check-ins.

“It turns on every two hours,” Ocepek explained, “and checks in with us, sending its coordinates by SMS to our phones to tell us where it is.” The messages also include Wi-Fi networks seen and other data. If a cell network can’t be reached, the device stores the data for the next check-in and shuts down. “So you can get into places where no amount of physical access could get you,” Ocepek said.

While the hardware is inexpensive, X-Force Red also invested hours in modifying the software used to make it work in a low-power environment. “We’re using our own custom [Linux] distribution that we made—we modified Tiny Core Linux and stuff like that,” Ocepek acknowledged. “So, there’s a lot going on here to make it work in this way, low power. But it’s doable.”

And if they could do it, Ocepek suggested, so could just about any determined attacker.

Road worrier

The check-in every two hours doesn’t just let the red team know when the package gets to its destination. It also has yielded some “weird unintended consequences,” Ocepek said. “They’ve turned into our own ‘wardriving'”—a mobile survey of Wi-Fi access points along the path of the shipment.

While en route, the warshipping rig picks up all the networks around it as it rides on the truck. It even picks up the in-flight Wi-Fi of aircraft in some cases. “Every time it turns on, you get all the access points that are around wherever it’s at,” Ocepek explained. “You’re getting all kinds of data on various networks until it gets to the client’s site. So if you wanted to war drive in an area that you’re not, that you don’t live in, you could send this through a carrier network and basically have it do it for you.”

That includes overseas locations, “no passport required,” said Henderson. “And the great thing is, that now with modern shipping mechanisms, you can actually predict where your package is going to be on a given day. So if I want to war drive, say, downtown London, I could ship a package to London and have it turn on on delivery day.”

More than just a good listener

The hack in the box can do more than just sniff for networks. Since it’s essentially just a platform, other sensors can be added to it, with interesting consequences.

Henderson had me pick a box up for demonstration. “If you were wearing an RFID badge, where would it be right now?” The answer, of course, was right up against the box—where a low-cost software-defined radio could read and clone the data in it for an attacker to create a counterfeit access badge. “Oh look, I just cloned your ass from 10,000 miles away,” Henderson said. And the box could be shipped to a specific person just to target their physical access credentials.

The method can also be used for offensive operations. Henderson said that when IBM shipped a device to a financial services company, “they said, ‘OK, what do you see?’ And we said, “We see three access points.'” One of them was not supposed to be there, and Henderson said the CISO at the company told him, “I’m going to need you to attack that one.”

“It was not supposed to be there,” Ocepek recounted. “They had a hidden SSID, too. So it was like, ‘What’s going on there? See what you can do.'”

The point of these exercises, Henderson said, was to get companies to “start considering packages untrusted in the same way that you would consider email or USB keys.”

If you eye that next Amazon box that arrives at the office a little more suspiciously, then, well, mission accomplished.