Facebook asked some users for their email passwords, because why not

As company executives try to rebrand Facebook as a privacy company, the company is still apparently struggling to instill a privacy culture internally and with third-party developers. As Kevin Poulson of the Daily Beast reported on April 2, some new Facebook users were being asked to provide both their email address and their email password in order to register accounts.

And in a blog post today, researchers from the cloud security firm UpGuard reported that they had discovered two publicly accessible caches of Facebook user data created by third-party applications that connected to the Facebook platform. Both caches were hosted by Amazon Web Services’ Simple Storage Service (S3) in the AWS public cloud.

Password, please

The email password practice was first noticed by a software developer and information security expert who goes by the handle “e-sushi”:

Hey @facebook, demanding the secret password of the personal email accounts of your users for verification, or any other kind of use, is a HORRIBLE idea from an #infosec point of view. By going down that road, you’re practically fishing for passwords you are not supposed to know! pic.twitter.com/XL2JFk122l

— e-sushi (@originalesushi) March 31, 2019

The requests were made to users with many Web-based email hosting services. Google’s Gmail was not among them, as Facebook used the OAuth protocol to verify Gmail accounts—so verification with an email password was not required.

In a response to the Daily Beast, a Facebook spokesperson said that the email passwords were not stored by Facebook. But given Facebook’s previous problems with logging passwords and retaining other personal data, that statement may be greeted with healthy skepticism.

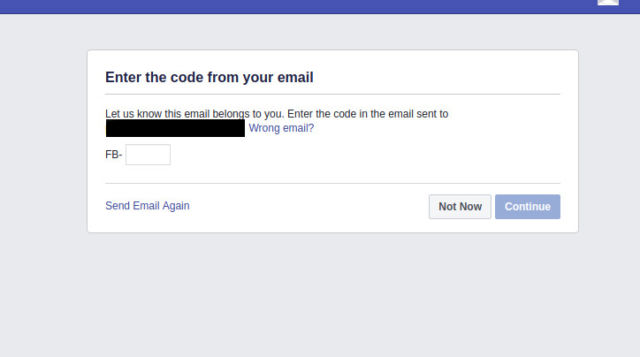

The Facebook spokesperson also said that the company was ending the practice of requesting email passwords for webmail accounts. A test by Ars Technica today confirmed that—using email accounts on Mail.com and other webmail services, we registered accounts and instead got a prompt for a code emailed to the email address provided.

Big buckets of nope

The user data exposures reported by UpGuard were connected to two different companies’ Facebook-related applications. The first, from Cultura Colectiva—a Mexican media company—was a 146 gigabyte store containing more than 540 million records, including Facebook account IDs and names and associated reactions, “likes,” and comments, among other things. The UpGuard researchers compared the scope of the contents to that collected by Cambridge Analytica.

The second cache, also found in an Amazon S3 bucket, was a database backup from “a Facebook-integrated app called ‘At the Pool,'” the researchers reported. The database included column labels suggesting the data included Facebook user IDs and names, friends, likes, photos, events, groups, location check-ins, and other profile data, including favorite music, books, movies, and interests. There was also a “password” column, but the passwords were “presumably for the ‘At the Pool’ app rather than for the user’s Facebook account,” UpGuard’s researchers reported. Still, these passwords could pose a risk if exposed—particularly if they had been re-used across other accounts.

The S3 buckets containing the data have been shut down or secured. For the Cultura Colectiva store, however, it took nearly four months from the date of first disclosure for the store to be secured. Cultura Colectiva never responded to emails alerting them to the exposed data. It wasn’t until today, when Facebook was contacted about the exposure by a journalist asking for comment, that the data store was secured. The backup for the “At the Pool” app was taken offline before UpGuard could notify the developers; the application is no longer active, and the company that owned the application may have ceased to exist.

Both of these cases show that while Facebook has promised to limit the ability of developers to extract personal data from its service in the wake of the Cambridge Analytica scandal, there are still third parties that have access to large volumes of Facebook data. And Facebook isn’t necessarily policing how it stores that data, despite the company’s new policies.