Apple’s AirDrop and password sharing features can leak iPhone numbers

Apple makes it easy for people to locate lost iPhones, share Wi-Fi passwords, and use AirDrop to send files to other nearby devices. A recently published report demonstrates how snoops can capitalize on these features to scoop up a wealth of potentially sensitive data that in some cases includes phone numbers.

Simply having Bluetooth turned on broadcasts a host of device details, including its name, whether it’s in use, if Wi-Fi is turned on, the OS version it’s running, and information about the battery. More concerning: using AirDrop or Wi-Fi password sharing broadcasts a partial cryptographic hash that can easily be converted into an iPhone’s complete phone number. The information—which in the case of a Mac also includes a static MAC address that can be used as a unique identifier—is sent in Bluetooth Low Energy packets.

The information disclosed may not be a big deal in many settings, such as work places where everyone knows everyone anyway. The exposure may be creepier in public places, such as a subway, a bar, or a department store, where anyone with some low-cost hardware and a little know-how can collect the details of all Apple devices that have BLE turned on. The data could also be a boon to companies that track customers as they move through retail outlets.

As noted above, in the event someone is using AirDrop to share a file or image, they’re broadcasting a partial SHA256 hash of their phone number. In the event Wi-Fi password sharing is in use, the device is sending partial SHA256 hashes of its phone number, the user’s email address, and the user’s Apple ID. While only the first three bytes of the hash are broadcast, researchers with security firm Hexway (which published the research) say those bytes provide enough information to recover the full phone number.

Below is a video of an attack:

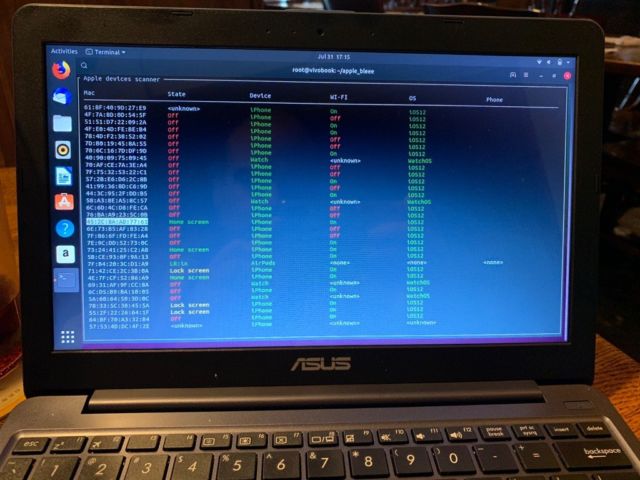

Hexway’s report includes proof-of-concept software that demonstrates the information broadcast. Errata Security CEO Rob Graham installed the proof-of-concept on a laptop that was equipped with a wireless packet sniffer dongle, and within a minute or two he captured details of more than a dozen iPhones and Apple Watches that were within radio range of the bar where he was working. The highlighted device in the middle of the picture below is his iPhone.

“It’s not too bad, but it’s still kind of creepy that people can get the status information, and getting the phone number is bad,” he said. It’s not likely, he added, that Apple can prevent phone numbers and other information from leaking, since they’re required—in some form, anyway—for devices to seamlessly connect with other devices a user trusts.

The MAC addresses shown in the image above aren’t the actual device numbers, but rather temporary MAC addresses that rotate regularly. But Graham said unlike iPhone and Apple Watch addresses, MAC addresses for Macintosh computers aren’t obfuscated this way. By broadcasting only partial hashes of phone numbers, email addresses, and AppleID, Apple is clearly making an effort to make data collection hard. But the reality of rainbow tables, automated word or number lists, and lightning-fast hardware means it’s often trivial to crack those hashes.

“This is the classic trade-off that companies like Apple try to make when balancing ease of use vs privacy/security,” independent privacy and security researcher Ashkan Soltani told Ars. “In general, automatic discovery protocols often require the exchange of personal information in order to make them work—and as such—can reveal things that could be considered sensitive. Most security and privacy minded folks I know disable automatic discovery protocols like AirDrop, etc just out of principle.”