Activists’ phones targeted by one of the world’s most advanced spyware apps

Mobile phones of two prominent human rights activists were repeatedly targeted with Pegasus, the highly advanced spyware made by Israel-based NSO, researchers from Amnesty International reported this week.

The Moroccan human rights defenders received SMS text messages containing links to malicious sites. If clicked, the sites would attempt to install Pegasus, which as reported here and here, is one of the most advanced and full-featured pieces of spyware ever to come to light. One of the activists was also repeatedly subjected to attacks that redirected visits intended for Yahoo to malicious sites. Amnesty International identified the targets as activist Maâti Monjib and human rights lawyer Abdessadak El Bouchattaoui.

Serial pwner

It’s not the first time NSO spyware has been used to surveil activists or dissidents. In 2016, United Arab Emirates dissident Ahmed Mansoor received text messages that tried to lure him to a site that would install Pegasus on his fully patched iPhone. The site relied on three separate zeroday vulnerabilities in iOS. According to previous reports from Univision, Amnesty International, and University of Toronto-based Citizen Lab, NSO spyware has also targeted:

- 150 people, including US citizens and opposition critics chosen by an ex-president of Panama

- 22 journalists and activists researching corruption in the Mexican government

- Two people—one an Amnesty International researcher and the other a dissident—in Saudi Arabia

A potent attack exploiting a vulnerability in both the iOS and Android versions of WhatsApp was used to install Pegasus, researchers said five months ago. Last week, Google also uncovered evidence NSO was tied to an actively exploited Android zeroday that gave attackers the ability to compromise millions of devices. It’s not known who the targets were in either of those attacks.

This week’s report said that the targeting of the two Morrocan human rights defenders began no later than November 2017 and likely lasted until at least July of this year. In 2017 and 2018, the men received text messages that contained links to sites including stopsms[.]biz and infospress[.]com, which Amnesty International previously said was part of NSO’s exploit infrastructure. Other domains included revolution-news[.]co (which Citizen Lab has identified as tied to NSO) and the previously unknown hmizat[.]co (which appears to impersonate Moroccan ecommerce company Hmizate).

Suspicious redirects

Then, starting this year, Monjib’s iPhone started being suspiciously redirected to malicious sites. An analysis of logs Safari stores of each visited link and the origin and destination of each visit showed the redirects happened after Monjib entered “yahoo.fr” in the address bar of his Safari browser. Under normal conditions, Safari would quickly be redirected to the encrypted link https://fr.yahoo.com/. But on at least four occasions, from March of this year to July, the activist was instead diverted to links including

hxxps://bun54l2b67.get1tn0w.free247downloads[.]com:30495/szev4hz

and

hxxps://bun54l2b67.get1tn0w.free247downloads[.]com:30495/szev4hz#048634787343287485982474853012724998054718494423286

.

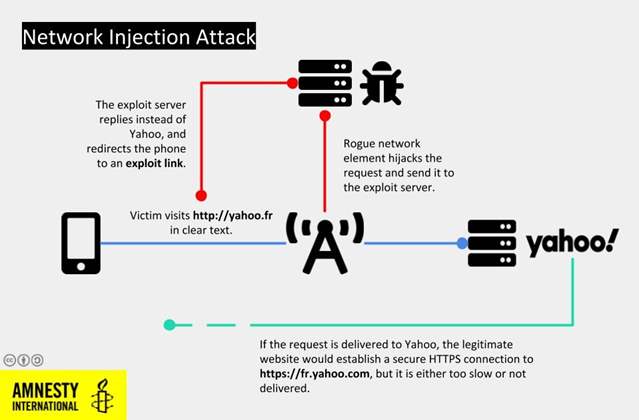

These redirections were possible only because the initial connection to Yahoo wasn’t protected by an encrypted HTTPS connection. In the redirection from July, Monjib again tried to access Yahoo, but instead of typing an address in the browser, he searched for “yahoo.fr mail” on Google. When he clicked the result, he landed on the correct site. Authors of this week’s report wrote:

We believe this is a symptom of a network injection attack generally called “man-in-the-middle” attack. Through this, an attacker with privileged access to a target’s network connection can monitor and opportunistically hijack traffic, such as Web requests. This allows them to change the behavior of a targeted device and, such as in this case, to re-route it to malicious downloads or exploit pages without requiring any extra interaction from the victim.

Such a network vantage point could be any network hop as close as possible to the targeted device. In this case, because the targeted device is an iPhone, connecting through a mobile line only, a potential vantage point could be a rogue cellular tower placed in the proximity of the target or other core network infrastructure the mobile operator might have been requested to reconfigure to enable this type of attack.

Because this attack is executed “invisibly” through the network instead of with malicious SMS messages and social engineering, it has the advantages of avoiding any user interaction and leaving virtually no trace visible to the victim.

We believe this is what happened with Maâti Monjib’s phone. As he visited yahoo.fr, his phone was being monitored and hijacked, and Safari was automatically directed to an exploitation server which then attempted to silently install spyware.

Amnesty International researchers said they believe at least one of the injections “was successful and resulted in the compromise of Maâti Monjib’s iPhone.” The researchers continued:

Whenever an application crashes, iPhones store a log file keeping traces of what precisely caused the crash. These crash logs are stored on the phone indefinitely, at least until the phone is synced with iTunes. They can be found in Settings > Privacy > Analytics > Analytics Data. Our analysis of Maâti Monjib’s phone showed that, on one occasion, all these crash files were wiped a few seconds after one of these Safari redirections happened. We believe it was a deliberate clean-up executed by the spyware in order to remove traces that could lead to the identification of the vulnerabilities actively exploited. This was followed by the execution of a suspicious process and by a forced reboot of the phone.

A preponderance of evidence

The researchers said they can’t prove the redirections were the work of NSO products or services, but they say evidence strongly suggests a link. The evidence includes similarities between the known NSO URLs contained in the SMS messages—such as

hxxps://videosdownload[.]co/nBBJBIP

and the URLs used in the redirects —such as

hxxps://bun54l2b67.get1tn0w.free247downloads[.]com:30495/szev4hz

. Both are composed of generic domain names followed by a pseudorandom alphanumeric string of seven to nine characters.

The researchers also found a similar network injection capability described in a document titled Pegasus—Product Description that was found in the 2015 hack of NSO competitor Hacking Team. The NSO document calls the redirect capability a “Tactical Network Element” and describes how a rogue cell tower could be used to identify a targeted phone and remotely inject and install Pegasus.

Amid growing criticism, NSO Group—which earlier this year was valued at $1 billion in a leveraged buyout by UK-based private equity firm Novalpina Capital—promised in September to follow a human rights policy based on these guiding principles. A key aspect of the policy was to “investigate whenever the company becomes aware of alleged unlawful digital surveillance and communication interception of NSO products.”

In a response to this week’s report, NSO officials wrote:

As per our policy, we investigate reports of alleged misuse of our products. If an investigation identifies actual or potential adverse impacts on human rights, we are proactive and quick to take the appropriate action to address them. This may include suspending or immediately terminating a customer’s use of the product, as we have done in the past.

While there are significant legal and contractual constraints concerning our ability to comment on whether a particular government agency has licensed our products, we are taking these allegations seriously and will investigate this matter in keeping with our policy. Our products are developed to help the intelligence and law enforcement community save lives. They are not tools to surveil dissidents or human rights activists. That’s why contracts with all of our customers enable the use of our products solely for the legitimate purposes of preventing and investigating crime and terrorism. If we ever discover that our products were misused in breach of such a contract, we will take appropriate action.

In an email, an NSO representative said appropriate action could include shutting down a customer’s access to the NSO system, which the company has done three times in the past.

Amnesty International, for its part, remains skeptical.

“In the absence of adequate transparency on investigations of misuse by NSO Group and due diligence mechanisms, Amnesty International has long found these claims spurious,” this week’s report said. “With the revelations detailed in this report, it has become increasingly obvious that NSO Group’s claims and its human rights policy are an attempt to whitewash rights violations caused by the use of its products.”