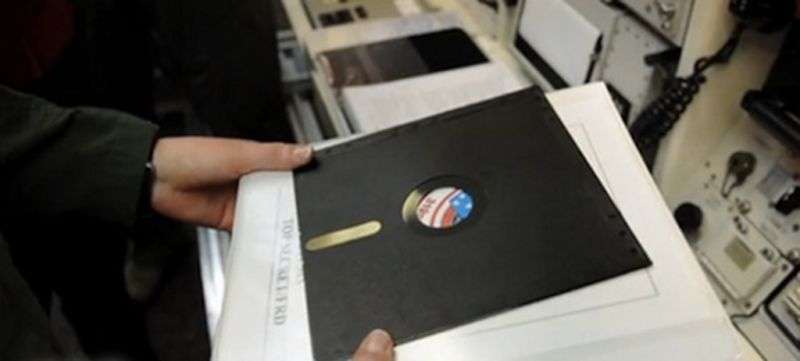

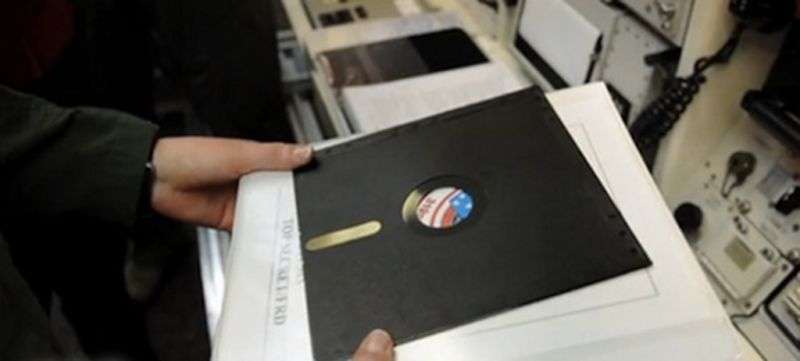

Air Force finally retires 8-inch floppies from missile launch control system

Five years ago, a CBS 60 Minutes report publicized a bit of technology trivia many in the defense community were aware of: the fact that eight-inch floppy disks were still used to store data critical to operating the Air Force’s intercontinental ballistic missile command, control, and communications network. The system, once called the Strategic Air Command Digital Network (SACDIN), relied on IBM Series/1 computers installed by the Air Force at Minuteman II missile sites in the 1960s and 1970s.

Those floppy disks have now been retired. Despite the contention by the Air Force at the time of the 60 Minutes report that the archaic hardware offered a cybersecurity advantage, the service has completed an upgrade to what is now known as the Strategic Automated Command and Control System (SACCS), as Defense News reports. SAACS is an upgrade that swaps the floppy disk system for what Lt. Col. Jason Rossi, commander of the Air Force’s 595th Strategic Communications Squadron, described as a “highly secure solid state digital storage solution.” The floppy drives were fully retired in June.

But the IBM Series/1 computers remain, in part because of their reliability and security. And it’s not clear whether other upgrades to “modernize” the system have been completed. Air Force officials have acknowledged network upgrades that have enhanced the speed and capacity of SACCS’ communications systems, and a Government Accountability Office report in 2016 noted that the Air Force planned to “update its data storage solutions, port expansion processors, portable terminals, and desktop terminals by the end of fiscal year 2017.” But it’s not clear how much of that has been completed.

While SACCS is reliable, it is obviously expensive and difficult to maintain when it fails. There are no replacement parts available, so all components must be repaired—a task that may require hours manipulating parts under a microscope. Civilian Air Force employees with years of experience in electronics repairs handle the majority of the work. But the code that runs the system is still written by enlisted Air Force programmers.