Egypt used Google Play in spy campaign targeting its own citizens, researchers say

Hackers with likely ties to Egypt’s government used Google’s official Play Store to distribute spyware in a campaign that targeted journalists, lawyers, and opposition politicians in that country, researchers from Check Point Technologies have found.

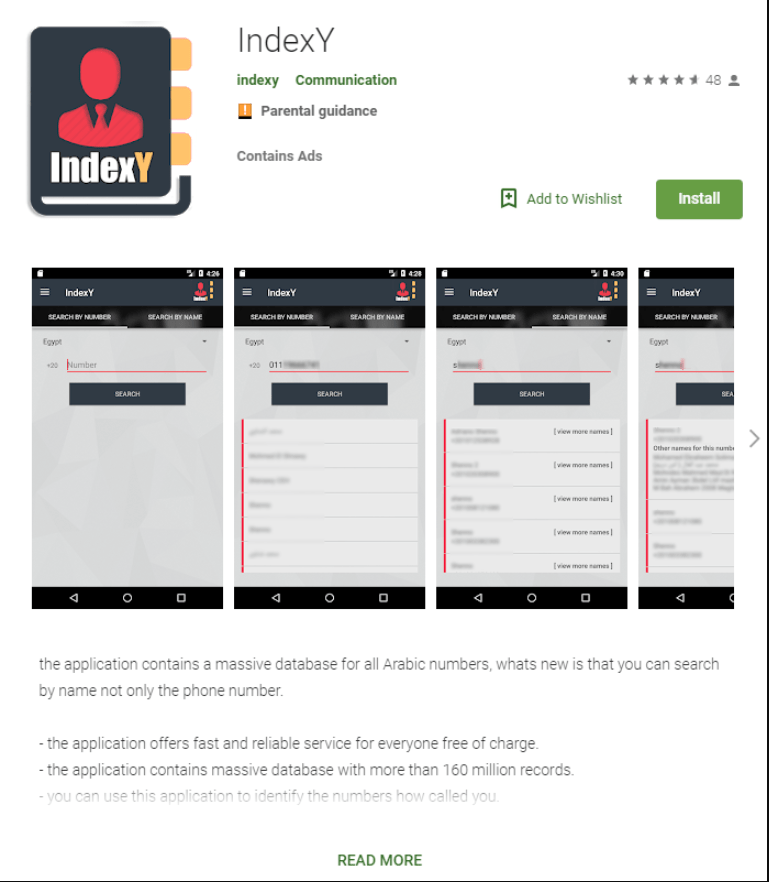

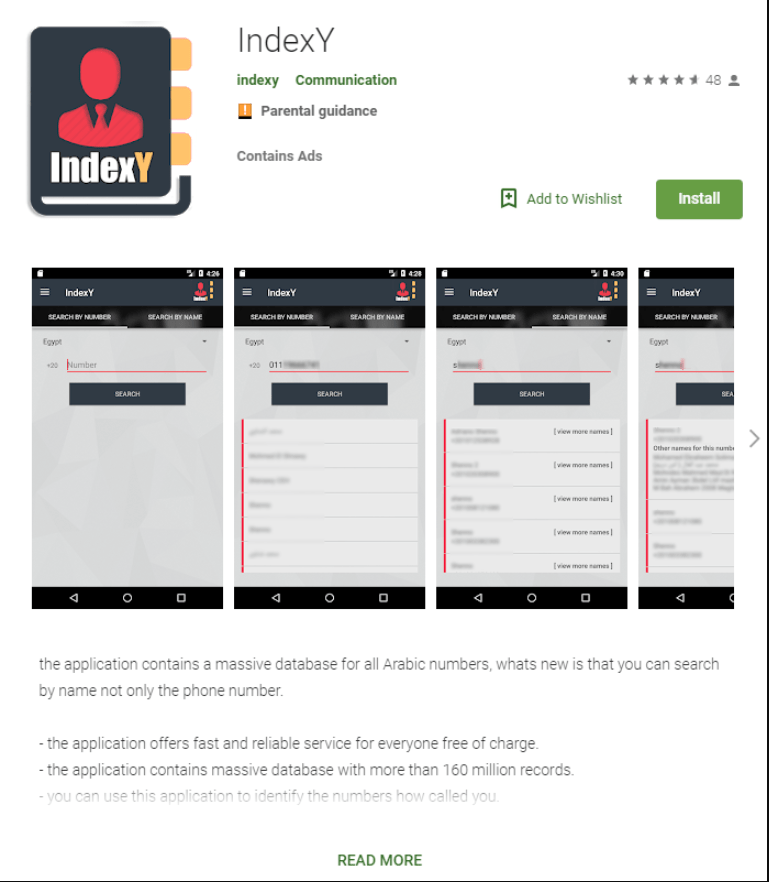

The app, called IndexY, posed as a means for looking up details about phone numbers. It claimed to tap into a database of more than 160 million Arabic numbers. One of the permissions it required was access to a user’s call history and contacts. Despite the sensitivity of that data, those permissions were understandable, given the the app’s focus on phone numbers. It had about 5,000 installations before Google removed it from Play in August. Check Point doesn’t know when IndexY first became available in Play.

Behind the scenes, IndexY logged whether each call was incoming, outgoing, or missed as well as its date and duration. Publicly accessible files left on indexy[.]org, a domain hardcoded into the app, showed not only that the data was collected but that the developers actively analyzed and inspected that information. Analysis included the number of users per country, call-log details, and lists of calls made from one country to another.

IndexY was one piece of a broad and far-ranging surveillance campaign that was first documented in March by Amnesty International. It targeted people who played adversarial roles to Egypt’s government and prompted warnings from Google to some of those targeted that “government-backed attackers are trying to steal your password.” Check Point found that, at the same time, Google was playing a key supporting role in the campaign.

Evading Google Play vetting… again

The attackers “were able to evade Google’s protections,” Lotem Finkelshtein, Check Point’s threat intelligence group manager, told Ars. “Getting into Google Play is something that gives the attacking infrastructure credibility.

Finkelshtein said that one of the ways the attackers evaded Google vetting of the app was that the analysis and inspection of the data happened on the attacker-designated server and not on an infected phone itself.

“Google couldn’t see the info that was collected,” he said.

Malicious and unwanted apps on Google Play have emerged as one of the most vexing security problems for the Android operating system. Discoveries such as this, this, this, and this, sometimes infecting hundreds of millions of devices, are a regular occurrence. Last month, Google Play had unwanted apps with nearly 336 million installs, according to security researcher Lukas Stefanko, although most of those apps were considered adware, as opposed to outright malware.

Bypassing 2FA

IndexY was one of at least three pieces of Android malware that Check Point tied to the campaign. A different app purported to increase the volume of devices, even though it had no such capability. Called iLoud 200%, it collected location data as soon as it was started. In the event it stopped running, iLoud was able to restart itself. Finkelshtein said that that app was distributed on third-party sites and was installed an unknown number of times.

Yet another app, called v1.apk, was submitted to Google’s VirusTotal malware detection service in February. It communicated with the domain drivebackup[.]co and appeared to be in an early testing phase.

As previously documented by Amnesty International, the campaign also used third-party apps that connected to Gmail and Outlook accounts using the OAuth standard. Finkelshtein said the apps had the ability to steal messages even when the targeted accounts were protected by two-factor authentication, which in addition to a password requires a physical security key or one-time password produced by a device in the target’s possession. The third-party apps were distributed in links sent in phishing and malicious spam messages.

The takeaway is that the attackers need not be sophisticated to succeed at surveilling their targets.

Check Point’s report concluded:

Following up on the investigation first conducted by Amnesty International, we revealed new aspects of the attack that has been after Egypt’s civil society since at least 2018… Whether it is phishing pages, legitimate-looking applications for Outlook and Gmail, and mobile applications to track a device’s communications or location, it is clear that the attackers are constantly coming up with creative and versatile methods to reach victims, spy on their accounts, and monitor their activity.