Badge life: The story behind DEFCON’s hackable crystal electronic badge

LAS VEGAS—There are many things that make the DEFCON conference stand above all other hacking conferences. It’s the largest, of course, with over 30,000 attendees, sprawling over four hotels in Las Vegas this year. And there are the Villages, each of them conferences unto themselves appealing to specific security and hacking communities. But the most visible, unifying part of DEFCON is its badges.

The DEFCON electronic badges—which for a time were used every other year because of the effort and budget that went into them—are typically the delivery vehicle for a unifying game. Last year’s badge was a sophisticated puzzle challenge that included a social element and even a built-in text-based adventure. This year’s badges, however, were both deceptively simple and cunningly complex, designed to get DEFCON attendees to interact with each other and explore the whole of the conference rather than falling too deeply into a badge rabbit hole.

Joe Grand, (AKA “Kingpin”), the designer of DEFCON’s very first electronic, hackable badges (used for DEFCONs 14 through 18) returned to the task for this year’s 27th edition of the event at the request of DEFCON founder Jeff Moss (“Dark Tangent”). Just before DEFCON kicked off, Grand spoke with Ars about this year’s badge design and the effort required to put together a real-world electronic quest for about 30,000 friends.

Badged for life

King said Moss “called me out of the blue at the end of December [2018] and he’s like, ‘Hey, do you want to do the DEFCON badge?’ Well, it was a decent amount of time… it would’ve been better to be like the day after last DEFCON.”

King agreed, as he had spent much of 2018 traveling to speak and teach, “and I wanted to stay at home… like this would be a great opportunity to stay at home, work on a project, I can see my family more, I won’t be on the road. Of course, that shows that I’d forgotten the difficulty of actually designing badges.” King acknowledged.

The task of turning out the DEFCON badge “is a full-time effort,” Grand said. “That’s why they call it ‘badge life’.”

Grand told Moss that he wanted to do something simple “that can appeal to as many people as possible, because the puzzles that have been done are amazing, but I didn’t want to exclude people. I kind of put myself in that mindset of like, what if I was attending DEFCON for the first time? What would that feel like?”

Delivery of the badges required for DEFCON 27 came down to the wire, and Grand had to push manufacturing straight from first working prototype to full production. It’s a minor technological miracle that the badges had a relatively low failure rate at the conference—and many of those failures were a result of the hacks performed by attendees.

Grand originally started off designing DEFCON badges as part of an effort “to bring awareness of hardware and hardware hacking to DEFCON,” he said. “In the beginning, we didn’t know how people would respond, so we did a simple kind of artistic badge. And people really liked it.”

After DEFCON 14, electronic badges began to gradually take on a life of their own. “Little by little, you’d see other badges starting to come up, with people creating their own for their parties,” Grand recalled. “And it really was exciting to see this growth. Then every year, I’d always compete with myself. I’m like, ‘what can I do better, what technique can I try, what new art thing can I try?’ And my design aesthetic has always been, even with professional products that I do, just very simple, effective things. Like I’m not a puzzle, my brain doesn’t work like a puzzle master.”

After his fifth year, as “badge life” blossomed in full, “I said I was never going do it again because I… had [already] spoken my mind, right? I had done the artwork that I wanted to do and shared that side of me with other people and whatever. But I’d always said if Jeff ever asked to me again to do it then I’ll do it.”

Magical crystals

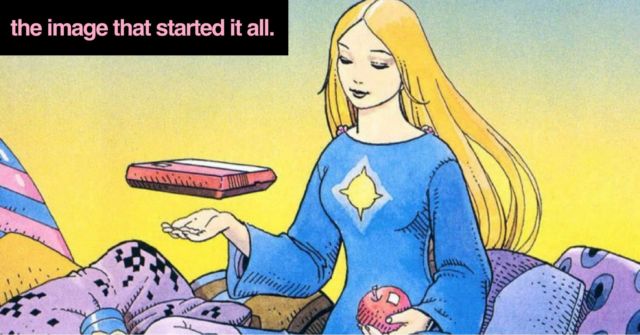

“Jeff sent me a picture of the theme for the conference, for his idea of the theme of ‘Technology’s Promise’,” Grand said. “And it was all pastel colors and clouds and a woman holding a laptop. It was an ad from the ’70s about like the future of technology—the good side of technology. Instead of technology owning you, it’s if technology helped you. And I saw that picture and I was just like, something was just like crystals. I don’t know, it seemed sort of new age-y.”

Moss later posted the image through DEFCON’s Twitter account.

Preparations are well underway for #DEFCON 27. Meetings are being met, plans are being planned, and the #defcon27theme is ready for its unveiling. pic.twitter.com/EwNfJK34A3

— DEFCON (@defcon) December 13, 2018

The theme was the flip-side of DEFCON 26’s “1983” tone—the “the inflection point between disorder and dystopia,” as Moss had put it in a Twitter post. The DEFCON 27 theme, Moss said, would be about “a major-key, blue-sky thoughtscape…a future where we have tamed some of the demons that plague us now, and tech supports and inspires instead of controlling and surveilling.”

That idea of crystals resulted in the deceptively simple design of the DEFCON 27 badge collection: a printed circuit board, itself a work of digital art, joined to a piece of hand-cut and hand-polished Brazilian quartz. For speaker, artist, press, and other “colored” badges, the quartz was dyed; rose quartz squares were used for the red “goon” (volunteer) badges. “Every single one of the 28,500 pieces that we’ve made is unique because it’s hand-cut crystal,” Grand said. “The quartz is going to vary in translucency or transparency. And so we put graphics behind it so you can sometimes see it.”

-

The circuit board that powered the DEFCON 27 badge game included parts never used for short manufacturing run electronic devices before, let alone badges.

-

The full array of badges, with the “goon” badge at the top.

-

All lit up: the LEDs on the badges as seen through the quartz crystals mounted on the front of them.

It was the badge as jewelry—the badges could be worn on a wristband sold in DEFCON’s “swag shop,” or as a headband, or (as I wore it) as a bolo tie. The badge lanyard could be pulled through “straps” that are “actually high current jumpers for industrial electronics” made in Japan, Grand explained. (Some attendees who clipped their badges to their lanyards with the provided metal hooks managed to short their badges out as a result.)

There was method to this madness. “There’s a bunch of badges everywhere,” Grand explained, “so [Moss] and I were like, well what if we move up the stack a little bit so the DEFCON badge has a single one and this fits onto the lanyard? So it will be kind of slide it through, and now your badge is up the lanyard so it’s more visible.”

Some of the components are fairly uncommon or had never been used in hackable badges before. “I tried to use some pretty ridiculous complex components,” Grand said.