Researchers crack open Facebook campaign that pushed malware for years

Researchers have exposed a network of Facebook accounts that used Libya-themed news and topics to push malware to tens of thousands of people over a five-year span.

Links to the Windows and Android-based malware first came to researchers’ attention when the researchers found them included in Facebook postings impersonating Field Marshal Khalifa Haftar, commander of Libya’s National Army. The fake account, which was created in early April and had more than 11,000 followers, purported to publish documents showing countries such as Qatar and Turkey conspiring against Libya and photos of a captured pilot that tried to bomb the capital city of Tripoli. Other posts promised to offer mobile applications that Libyan citizens could use to join the country’s armed forces.

According to a post published on Monday by security firm Check Point, most of the links instead went to VBScripts, Windows Script Files and Android apps known to be malicious. The wares included variants of open source remote-administration tools with names including Houdina, Remcos, and SpyNote. The tools were mostly stored on file-hosting services such as Google Drive, Dropbox, and Box.

The postings by the fake Haftar were riddled with typos, misspellings, and grammatical errors. The spelling mistakes in particular gave Check Point researchers a high degree of confidence that the content was generated by an Arabic speaker, since translation engines that would have converted the text from another language would have been unlikely to introduce the errors.

Tip of the iceberg

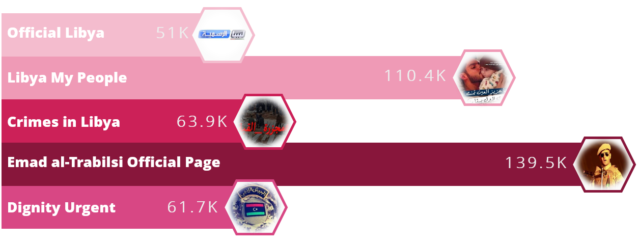

When searching for other sources that made the same mistakes, the researchers found more than 30 Facebook pages, some active since as early as 2014, that had been used to spread the same malicious links. The top-five most popular pages were collectively followed by more than 422,000 Facebook accounts, as shown in the graphic below:

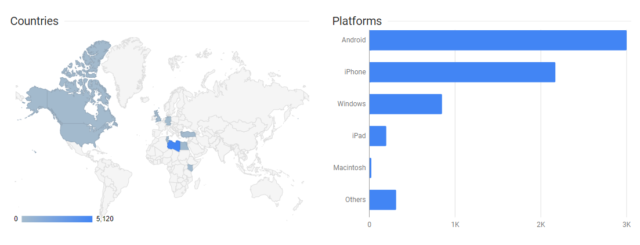

The attacker used URL-shortening services to generate most of the links. That allowed Check Point researchers to determine how many times a given link had been clicked and from what geographic region. The majority of the links had thousands of clicks, mostly from around the time the links were created and shared. The data also shows that Facebook pages were the most common source of the links, indicating that the social network was the most widely used vector in the campaign. Most of the clicks, meanwhile, came from Libya, although some affected machines were also located in Europe, the US, and Canada.

The following figures show one link getting about 6,500 clicks, with 5,120 of them coming from Libya:

Virtually all of the malware pushed during the five-year campaign connected to command and control servers located at drpc.duckdns[.]org and libya-10[.]com[.]ly. A Whois search showed that the latter domain was registered to someone using the email address drpc1070@gmail.com. That same email address was used to register other domains, including dexter-ly.space and dexter-ly.com.

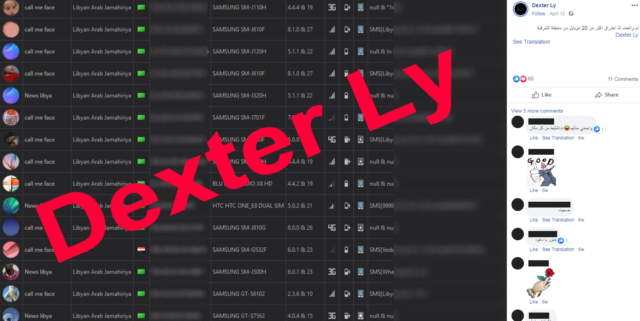

The name “Dexter Ly” led the researchers to yet another Facebook account. The new account repeated the same typos found in the earlier pages, prompting the researchers to assess with high confidence that all the pages are the work of the same person or group. The newly discovered account also openly shared details of the malicious campaign, including screenshots from the panels where the infected devices were managed:

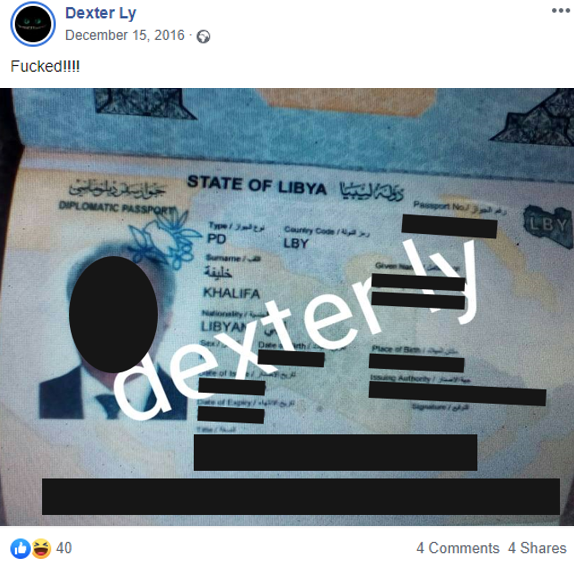

The Facebook account also published sensitive information that appears to have come from some of the infected targets. The data included secret documents belonging to Libya’s government, emails, phone numbers belonging to officials, and pictures of the officials’ passports:

Monday’s post said that Facebook removed the pages and accounts after Check Point researchers privately reported the campaign.

“These Pages and accounts violated our policies and we took them down after Check Point reported them to us,” Facebook officials said in a statement. “We are continuing to invest heavily in technology to keep malicious activity off Facebook, and we encourage people to remain vigilant about clicking on suspicious links or downloading untrusted software.”

The statement didn’t explain why Facebook’s heavy investment wasn’t enough for the company to detect the campaign on its own.

While the campaign has been disrupted, its discovery helps underscore how even operations with modest resources can be effective.

“Although the set of tools which the attacker utilized is not advanced nor impressive per se, the use of tailored content, legitimate websites and highly active pages with many followers made it much easier to potentially infect thousands of victims,” the researchers wrote. “The sensitive material shared in the ‘Dexter Ly’ profile implies that the attacker has managed to infect high profile officials as well.”