Baltimore ransomware perp pinky-swears he didn’t use NSA exploit

Over the past few weeks, a Twitter account that has since been confirmed by researchers to be that of the operator of the ransomware that took down Baltimore City’s networks May 4 has posted taunts of Baltimore City officials and documents demonstrating that at least some data was stolen from a city server. Those documents were posted in response to interactions I had with the ransomware operator in an attempt to confirm that the account was not a prank.

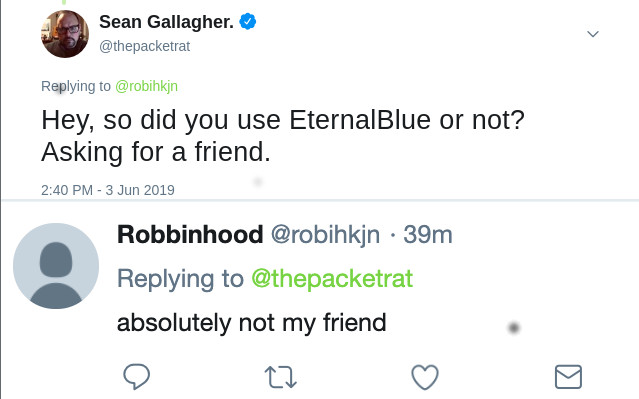

In their last post before the account was suspended by Twitter yesterday, the operator of the Robbinhood account (@robihkjn) answered my question, “Hey, so did you use EternalBlue or not?”:

absolutely not my friend

The account was shut down after its operator posted a profanity and racist-tinged final warning to Baltimore City Mayor Bernard “Jack” Young that he had until June 7 to pay for keys to decrypt files on city computers. “In 7 Jun 2019 that’s your dead line,” the post stated. “We’ll remove all of things we’ve had about your city and you can tell other [expletives] to help you for getting back… That’s final dead line.” The same messages have been posted to the Web “panel” associated with the Baltimore ransomware, according to Joe Stewart, independent security consultant working on behalf of the cloud security firm Armor, and Eric Sifford, security researcher with Armor’s Threat Resistance Unit (TRU).

Proof of compromise

-

A document posted by the Baltimore ransomware operator, with personal data redacted, shows it was faxed to the city on May 3.

-

The Tor Web “pane” used in conjunction with the Baltimore Robbinhood ransomware attack.

-

A screenshot of the Tor-based ransomware website tied to the Baltimore ransomware attack, showing the link to the Robbinhood Twitter account.

The Robbinhood account’s initial post included extremely low-resolution images to prove that the individual or group behind the account had access to Baltimore City’s network prior to the ransomware being triggered. That image included passwords to a shared network directory for use in installing an older version of Symantec Endpoint Protection, an image of a faxed subpoena for a lawsuit against the mayor’s office, and what appears to be lists of user names and hashed passwords for a number of city employee accounts.

But the age of the documents and their resolution led some (including me) to question their authenticity. I replied to the post, stating those doubts.

On May 28, the person or persons behind the Robbinhood account responded by posting another file to a file sharing site and sharing the link. That file, downloaded by researchers at Armor, was a PDF of a faxed document related to another lawsuit against the city, dated May 3. The PDF’s metadata indicated that it was created by a networked Xerox fax machine on Baltimore City’s network. Another document posted on June 3 was a cover sheet from a fax regarding a workman’s compensation claim sent to the mayor’s office the week before.

The final confirmation that the Twitter account was linked to the ransomware attack was provided when the operators posted a link to the Twitter account along with the same final warning to the Tor-based Web panel set up for communications with the city, shown above. (The “you” in the conversation is either a city employee or security researcher.)

Ransomware samples analyzed by researchers and by Ars don’t offer any hints of how they were distributed. The ransomware sample from Baltimore is virtually identical to previous versions of Robbinhood obtained by researchers—a 2.9MB Windows executable written in the Go language and compiled as a Windows executable—does not include any code used to seek other vulnerable machines, and it fails to run if a public key hasn’t been deposited in the right location on the targeted computer. While the ransomware uses RSA encryption, it includes functions from the entire Go cryptography library. Artifacts within the code show it was compiled from source by someone with a Windows user name of “valery.”

Honor among thieves

The statement by Robbinhood’s operator that EternalBlue was not used to spread the ransomware within Baltimore City’s networks is obviously not hard evidence that the NSA exploit exposed by Shadow Brokers wasn’t used in the attack. There are a number of reasons the attacker would lie about it—including boosting their marketing message. Stewart and Sifford said that they believe the attacker is likely using the attack on Baltimore as a way to get publicity for offering Robbinhood as a ransomware-as-a-service offering, allowing others to rent the ransomware to extort others. Revealing the exploits used to spread the ransomware would be, in that case, a horrible business move.

Making such a big publicity play over a ransomware target is rare in such attacks, as is posting proof of compromised files, because that is generally bad for business. Organizations that pay ransomware demands usually do so to avoid publicity and do so under the assumption that none of their data was stolen. But government targets are less likely to pay, and seeking publicity may be a way to build political pressure on the target to pay up.

There’s another possible explanation of the behavior of the Robbinhood attacker: they may have been in Baltimore’s network for some time and released the ransomware only after extracting whatever value they could from network access. In that case, there’s no telling what other data was taken from the city’s network.