Researchers discover state actor’s mobile malware efforts because of YOLO OPSEC

WASHINGTON, DC —At the Shmoocon security conference here on January 19, two researchers from the mobile security provider Lookout revealed the first details of a mobile surveillance effort run by a yet-to-be named state intelligence agency that they had discovered by exploring the command-and-control infrastructure behind a novel piece of mobile malware. In the process of exploring the malware’s infrastructure, Lookout researchers found iOS, Android, and Windows versions of the malware, as well as data uploaded from a targeted phone’s WhatsApp data. That phone turned out to be one that belonged to one of the state-backed surveillance effort—and the WhatsApp messages and other data found on the server provided a nearly full contact list for the actors and details of their interactions with commercial hacking companies and eventual decision to build their own malware.

Lookout has not revealed the country behind the malware, as the highly targeted collection campaign is still active and exposing it would burn the company’s ability to block the malware and continue to collect intelligence about the organization. Lookout’s Andrew Bliach and Michael Flossman, who presented the findings at Shmoocon, have provided some of the details they have obtained in a blog post, however—and they provide a fascinating look at how a reasonably well-funded state-sponsored intelligence-gathering operation works.

The communications data was left in the open on the infrastructure discovered by Bliach and Flossman; apparently, operational security was not a major concern for the malware operations team behind the effort. As a result, the researchers were able to view communications between members of that team and representatives of a number of zero-day and hacking-services providers as they explored purchasing the tools needed to gain access to their targets. “These messages were uncovered during an in-depth investigation and reverse-engineering effort into the infrastructure and malware tooling that this group built themselves.” Flossman and Bliach wrote in their follow-up blog. “These message also revealed many potential 0-days that a buyer could purchase along with their cost, effectiveness, and seller guarantee for both mobile and desktop operating systems.”

The state-funded group had a budget of $23 million, based on the communications uncovered. They had communications with a number of exploit vendors in 2017, including NSO Group, Verint, FinFisher, HackingTeam, IPS, Expert Team, and Wolf Intelligence, among others.

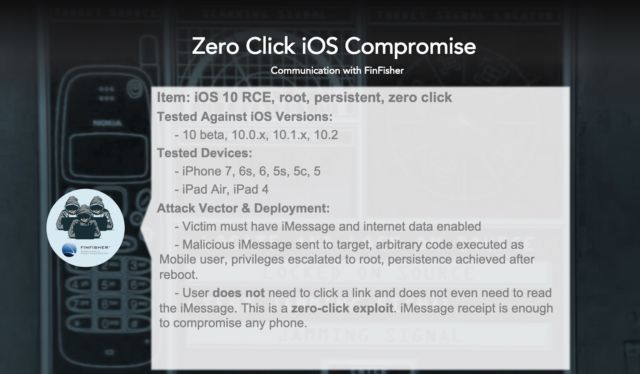

FinFisher offered a “zero click” iOS exploit that used a malicious iMessage message to execute code on the targeted iOS device, gain root privileges on the phone, and establish persistent access that would survive device reboots. Another bidder, a seller identifying themselves as an Estonian firm called “Arity Business Inc.,” offered a remote code-execution exploit of Android’s Mediaserver effective in Android versions 4.4.4 through 7.1, tested on HTC, Samsung, ASUS, Motorola, Xiaomi, LG, Sony, and Huawei handsets for the low, low price of $900,000–but just the exploit itself, without tools to weaponize it. NSO Group offered an SMS-based attack that required no interaction by the target, but recommended that it only be used at night “because the [web] browser itself opens for a few seconds.”

After a review of bids and testing the capabilities of some of the exploits offered, the team decided to build their own malware. “This is the only inexpensive way to get to the iPhone, except for the [Israeli] solution for 7 million and that’s only for WhatsApp,” explained one team member in a message. “We still need Viber, Skype, Gmail, and so on.” The same was true of the Android and Windows malware and the back-end tools used to manage the campaign. Rather than using zero-day exploits, the organization relied on a combination of physical access, spear-phishing, and other techniques to inject their espionage tools onto the targeted devices.

Bliach and Flossman found that their efforts were highly effective—”We discovered several hundred custom malware samples attributed to them that have collected what we estimate to be 50GB of exfiltrated data.” But the operational security mistakes made by the group has given the researchers a lengthy look into their ongoing operations. “This access and level of insight show how creative some adversaries have to be in the development of their surveillance tooling,” the Lookout researchers wrote in their follow-up post.

The research also highlights how nation-state organizations of all sizes and capabilities now have relatively easy access to surveillance capabilities from commercial sources and can develop ongoing capabilities on relatively meager budgets. The same tools, if mishandled by state organizations, could easily be obtained by and incorporated into criminal activities.