Massive scale of Russian election trolling revealed in draft Senate report

A report prepared for the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence (SSCI) due to be released later this week concludes that the activities of Russia’s Internet Research Agency (IRA) leading up to and following the 2016 US presidential election were crafted to specifically help the Republican Party and Donald Trump. The activities encouraged those most likely to support Trump to get out to vote while actively trying to spread confusion and discourage voting among those most likely to oppose him. The report, based on research by Oxford University’s Computational Propaganda Project and Graphika Inc., warns that social media platforms have become a “computational tool for social control, manipulated by canny political consultants, and available to politicians in democracies and dictatorships alike.”

In an executive summary to the Oxford-Graphika report, the authors—Philip N. Howard, Bharath Ganesh, and Dimitra Liotsiou of the University of Oxford, Graphika CEO John Kelly, and Graphika Research and Analysis Director Camille François—noted that, from 2013 to 2018, “the IRA’s Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter campaigns reached tens of millions of users in the United States… Over 30 million users, between 2015 and 2017, shared the IRA’s Facebook and Instagram posts with their friends and family, liking, reacting to, and commenting on them along the way.”

While the IRA’s activity focusing on the US began on Twitter in 2013, as Ars previously reported, the company had used Twitter since 2009 to shape domestic Russian opinion. “Our analysis confirms that the early focus of the IRA’s Twitter activity was the Russian public, targeted with messages in Russian from fake Russian users,” the report’s authors stated. “These misinformation activities began in 2009 and continued until Twitter began closing IRA accounts in 2017.”

Of course, because of the nature of the data provided to the researchers to work with, there wasn’t really any way to see if that sort of behavior happened on other social media platforms. Camille François explained to Ars in a phone view that Facebook had only provided English-language data for the accounts identified as IRA-operated, and no data that didn’t relate specifically to targeting US politics. “We didn’t have that in the Facebook data, but it doesn’t mean it never existed,”François noted.

Once the US-focused campaign began, it quickly evolved into a “multi-platform strategy,” the authors wrote, encompassing Facebook, Instagram, YouTube, and other platforms. “The IRA accounts actively engaged with disinformation and practices common to Russian ‘trolling.’ Some posts referred to Russian troll factories that flooded online conversations with posts, others denied being Russian trolls, and some even complained about the platforms’ alleged political biases when they faced account suspension.”

François said that because Facebook was out ahead of the other platforms in terms of shutting down IRA accounts, the company was the target of such disingenuous protests. “You see a period of months where they’re still active on other platforms, and those accounts are using other platforms to direct traffic to other sites that they controlled,” she explained. “The accounts were mocking ‘Russian interference’ and protesting the account suspensions.” In one case, François recounted, a fake Black Lives Matter account on Twitter complained about the shutting down of a Facebook page and accused Facebook of being “white supremacist.”

Mostly organic

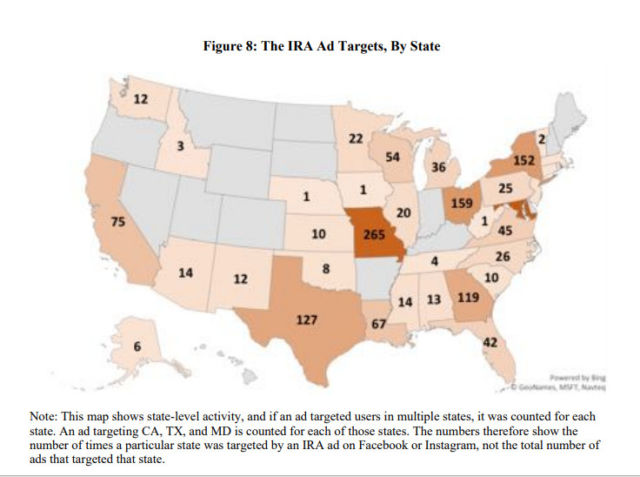

While there were bursts of advertising activity, “the most far-reaching IRA activity is in organic posting, not advertisements,” the authors noted. And the IRA’s aim, the researchers found, was to “polarize the US public and interfere in elections by campaigning for African-American voters to boycott elections or follow the wrong voting procedures in 2016, and more recently for Mexican American and Hispanic voters to distrust US institutions; encouraging extreme right-wing voters to be more confrontational; and spreading sensationalist, conspiratorial, and other forms of junk political news and misinformation to voters across the political spectrum.”

That activity seemed to increase even after the IRA was called out for its interference in the 2016 election. In fact, advertising volumes peaked in April of 2017 (when the US and allies launched cruise missile attacks against alleged Syrian chemical weapons facilities). And the IRA shifted its efforts to Instagram and Facebook more significantly after the 2016 election.

Uncooperative witnesses

The SSCI provided the data used by the researchers, which was submitted to the Senate by each of the major social media platform providers—Google, Facebook, and Twitter. But the format of the data handed over made analysis difficult, the researchers noted. Facebook only handed over data to the Senate committee on 76 accounts tied to advertising purchases and not those that were used to make posts. Google only provided content posted on YouTube identified as being associated with the Internet Research Agency’s campaign and not metadata for those posts or their associated accounts.

“There were important limitations in the data these platforms provided, and even though we repeatedly submitted requests for further data, we were not provided with additional data,” Dr. Liotsiou told Ars Technica in an email. “For example, the platforms did not provide any data on the characteristics of the users who engaged with IRA content, such as age groups, locations at the state level, race, education, or other demographic information, which would have been very useful.”

Furthermore, Liotsiou said, Google “provided data in non-machine-readable format—images of ad text and PDFs of spreadsheets, rather than the original ad text and spreadsheets in standard machine-readable formats like text files, CSV files, or JSON files.” And the data came from accounts the companies themselves had identified as IRA accounts, she noted. “It was not explained anywhere how the social media platforms determined that those were IRA accounts,” Liotsiou said. “We did request that information but received no response.”

Twitter’s limits on mining its timeline made independent research of the IRA’s activities difficult, the researchers noted. “Twitter used to provide researchers at major universities with access to several APIs but has withdrawn this and provides so little information on the sampling of existing APIs that researchers increasingly question its utility for even basic social science,” the authors of the report wrote. In October, Twitter published a dump of tweets by the accounts that Twitter’s Trust and Safety team identified as being part of Russian and Iranian propaganda operations, but the company concealed the identities of many of the accounts in order to protect the identities of individuals whose accounts may have been compromised, Twitter executives said at the time.

The report authors described their dilemma in their findings:

Facebook provides an extremely limited API for the analysis of public pages but no API for Instagram. Facebook provided the US Senate with information on the organic post data of 81 Facebook pages, and the data on Facebook ads bought by 76 accounts. Twitter’s data contribution covered activity in multiple languages, but Facebook’s data contribution focuses on activity only in English. Facebook chose not to disclose data from IRA Profiles or Groups and only shared organic post data from a small number of Pages with the Committee. Google chose to supply the Senate committee with data in a non-machine-readable format. The evidence that the IRA had bought ads on Google was provided as images of ad text and in PDF format whose pages displayed copies of information previously organized in spreadsheets.

The authors noted that the difficulties they faced in the process of investigating IRA activities “also allowed us—as researchers—to develop some recommended best practices for social media firms that want to hold the public trust.” They urged social media platforms to provide “an open and consistent API that allows researchers to analyze important trends in public life to data scientists.”